[译][论文] LLaMA:开放和高效的基础语言模型集(Meta/Facebook,2022)

译者序

本文翻译自 2022 年 Meta(facebook)的大模型论文: LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models。

作者阵容:Hugo Touvron, Thibaut Lavril, Gautier Izacard, Xavier Martinet, Marie-Anne Lachaux, Timothée Lacroix, Baptiste Rozière, Naman Goyal, Eric Hambro, Faisal Azhar, Aurelien Rodriguez, Armand Joulin, Edouard Grave, Guillaume Lample。

一些工程信息:

-

LLaMA 只使用公开可用数据集进行训练,模型已开源;

- 基于 transformer 架构;

- 训练数据集大小:1.4T 个 tokens;

- 参数范围

7B~65B;

-

使用更多 token 进行训练,而不是狂堆参数,一样能取得不错的性能。

- LLaMA-13B 在大多数基准测试中优于 GPT-3(175B);

-

用户更想要的可能是一个推理速度最快而不是训练速度最快的模型;此时模型大小就非常重要,

- LLaMA 可以在单个 GPU 上运行;

- LLaMA-13B 可以在单个 V100 上运行;

-

训练成本

- 2048 个 A100 80GB GPU 上,开发和训练约 5 个月;

- 训练 65B 模型时,在 2048 个 A100 80GB GPU 上能处理约

380 tokens/second/GPU,因此 1.4T token 的数据集训练一次大约需要 21 天; - 耗能约 2638 MWh,折算排放 1015 吨 CO2。

水平及维护精力所限,译文不免存在错误或过时之处,如有疑问,请查阅原文。 传播知识,尊重劳动,年满十八周岁,转载请注明出处。

以下是译文。

- 译者序

- 摘要

- 1 引言

- 2 方法(Approach)

- 3 主要结果(Main results)

- 4 指令微调(Instruction Finetuning)

- 5 Bias, Toxicity and Misinformation

- 6 碳足迹(Carbon footprint)

- 7 相关工作(Related work)

- 8 总结

- 致谢

- 参考文献

- 附录(略)

摘要

本文介绍 LLaMA,一个包含 7B~65B(70~650 亿)

参数的基础语言模型集(a collection of foundation language models)。

我们用数万亿个(trillions of) token

训练这些模型,证明了使用公开数据集就能训练出最先进的模型,

而并非必须使用专有和私有数据集。特别是,LLaMA-13B 在大多数基准测试中优于 GPT-3(175B)

,而 LLaMA-65B 则与最佳模型 Chinchilla-70B 和 PaLM-540B 相当。

我们已经将所有模型开源,供社区研究。

1 引言

在大规模文本语料库(massive corpora of texts)上训练的大型语言模型 (Large Languages Models, LLM),已经有能力根据给定的文本指令(textual instructions) 或示例(a few examples)执行新任务(Brown 等,2020)。

这些 few-shot 属性首先出现在将模型扩展到足够大的规模时(Kaplan 等,2020), 在此之后,出现了很多进一步扩展这些模型的工作(Chowdhery 等,2022;Rae 等,2021), 它们都遵循了这样一个假设:更多的参数将产生更好的性能。 然而,Hoffmann 等(2022)的最新工作表明,对于给定的算力预算(compute budget), 最佳性能并非来自那些最大的模型,而是来自那些在更多数据上训练出来的较小模型。

“few-shot” 指一个模型有能力根据给定的少量示例去执行其他的类似任务的能力。译注。

1.1 大模型训练:更多参数 vs 更大的数据集

Hoffmann 等(2022)提出 scaling laws,目标是针对给定的训练(training) 算力预算,如何最佳地扩展(scale)数据集和模型大小。但是,

- 这个模型没有考虑推理(inference)预算,在提供大规模推理时,这一点尤其重要: 在这种情况下,给定一个性能目标,我们更想要的是一个推理速度最快而非训练速度最快的模型。

- 对于一个给定的性能要求,训练一个大模型(a large model)可能是一种更便宜的方式; 但对于最终的推理来说,较小的模型+更长的训练时间(a smaller one trained longer)反而更实惠。 例如,Hoffmann 等(2022)建议用 200B tokens 来训练 10B 模型,但我们发现即使在 1T 个 token 之后,7B 模型的性能仍在随着 token 的增多而提高。

1.2 LLaMA:减少参数,增大数据集

本文的重点是:对于给定的不同推理预算(inference budgets),

通过使用更多 token 进行训练的方式(超过业内常用的 token 规模)

来获得最佳的性能(the best possible performance)。

由此得到的模型我们称为 LLaMA。

LLaMA 的参数范围在 7B ~ 65B,性能则与目前业界最佳的一些大语言模型相当。

例如,

- LLaMA-13B 在大多数基准测试中优于 GPT-3,

尽管参数连后者的

10%都不到; - LLaMA 可以在单个 GPU 上运行, 因此使大模型的获取和研究更容易,而不再只是少数几个大厂的专利;

- 在高端系列上,LLaMA-65B 也与最佳的大语言模型(如 Chinchilla 或 PaLM-540B)性能相当。

与 Chinchilla、PaLM、GPT-3 不同,我们只使用公开数据(publicly available data), 因此我们的工作是开源兼容的;

- 相比之下,大多数现有模型依赖于不公开或没有文档的数据(not publicly available or undocumented),例如 “Books–2TB” 和 “Social media conversations”;

- 也存在一些例外,例如 OPT(Zhang 等,2022)、GPT-NeoX(Black 等,2022)、BLOOM(Scao 等,2022)和 GLM(Zeng 等,2022), 但它们的性能都无法与 PaLM-62B 或 Chinchilla 相比。

1.3 内容组织

本文接下来的内容组织如下:

- 描述我们对 Transformer 架构(Vaswani 等,2017)所做的改动,以及我们的训练方法:

- 给出 LLaMA 的性能,基于标准基准测试与其他 LLM 进行比较;

- 使用 responsible AI 社区的最新基准测试,揭示 LLaMA 模型中存在的一些偏见和毒性(biases and toxicity)。

2 方法(Approach)

我们的训练方法与前人的一些工作(Brown 等,2020;Chowdhery 等,2022)类似, 并受到 Chinchilla scaling laws(Hoffmann 等,2022)的启发。 我们使用一个标准的 optimizer 在大量文本数据上训练大型 Transformers。

2.1 预训练数据(Pre-training Data)

2.1.1 数据集

训练数据集有几种不同来源,涵盖了多个领域,如表 1 所示。

| 数据集 | 占比 | 迭代次数(Epochs) | 数据集大小(Disk size) |

| CommonCrawl | 67.0% | 1.10 | 3.3 TB |

| C4 | 15.0% | 1.06 | 783 GB |

| Github | 4.5% | 0.64 | 328 GB |

| Wikipedia | 4.5% | 2.45 | 83 GB |

| Books | 4.5% | 2.23 | 85 GB |

| ArXiv | 2.5% | 1.06 | 92 GB |

| StackExchange | 2.0% | 1.03 | 78 GB |

表 1:预训练数据。

其中 epochs 是用 1.4T tokens 预训练时的迭代次数。用 1T tokens 预训练时也是用的这个数据集比例。

这里的数据集大部分都是其他 LLM 训练用过的, 但我们只用其中公开可得(publicly available)的部分,并且要保持开源兼容(compatible with open sourcing)。 因此最后得到的就是一个混合数据集。

English CommonCrawl [67%]

我们使用 CCNet pipeline(Wenzek 等,2020)对 2017~2020 的五个 CommonCrawl dumps 进行预处理。

- 在行级别(line level)上对数据去重,

- 使用 fastText 线性分类器进行语言识别,去掉非英文网页,

- 使用 ngram 语言模型过滤掉一些低质量内容。

此外,我们还训练了一个线性模型,将页面分为两类:

- 被 Wikipedia 引用过的网页;

- 没有被 Wikipedia 引用过的(随机采样网页);

并将第二类丢弃。

C4 [15%]

在前期探索性实验中,我们观察到使用多样化的预处理 CommonCrawl 数据集可以提高性能。 因此,我们将公开可用的 C4 数据集(Raffel 等,2020)也包含到了训练数据中。

对 C4 的预处理也是去重和语言识别:与 CCNet 的主要区别在于质量过滤(quality filtering), 主要依赖于启发式方法(heuristics),例如是否存在标点符号或网页中单词和句子的数量。

Github [4.5%]

使用了 Google BigQuery 上公开可用的 GitHub 数据集,但仅保留其中用 Apache、BSD 和 MIT license 的项目。 此外,

- 基于行长度(line length),字母或数字字符(alphanumeric characters)比例等,用启发式方法过滤掉低质量文件;

- 使用正则表达式删除一些模板段落(boilerplate),例如 headers;

- 在文件级别上使用精确匹配对得到的数据集进行去重。

Wikipedia [4.5%]

使用了 2022 年 6 月至 8 月的一部分 Wikipedia dumps, 覆盖 20 种语言(use either the Latin or Cyrillic scripts):bg、ca、cs、da、de、en、es、fr、hr、hu、it、nl、pl、pt、ro、ru、sl、sr、sv、uk。

删掉了其中的超链接、注释和其他 formatting boilerplate。

Gutenberg and Books3 [4.5%]

训练数据集中包含两个书籍语料库:

- Gutenberg Project:公版书(public domain books);

- Books3 section of ThePile(Gao 等,2020):一个用于训练大语言模型的公开可用数据集。

在书级别(book level)去重,内容超过 90% 重复的书会被剔除出去。

ArXiv [2.5%]

为了让训练数据集包含一定的科学数据(scientific data),我们对一些 arXiv Latex 文件做处理之后加到训练数据集。

- 按照 Lewkowycz 等(2022)的方法,删除了 the first section 之前的所有内容以及参考文献,

- 从 .tex 文件中删除了注释,

- 对作者编写的定义和宏(definitions and macros written by users)做了内联展开(inline-expand),使得论文更加一致(increase consistency across papers)。

Stack Exchange [2%]

Stack Exchange 是一个高质量的问答网站,涵盖了从计算机科学到化学等各种领域。 我们的训练数据集包括了一个 Stack Exchange dump,

- 保留其中最大的 28 个网站的数据,

- 从文本中删除了 HTML tags ,

- 按分数(从高到低)对答案进行了排序。

2.1.2 Tokenizer(分词器)

我们使用 bytepair encoding(BPE)算法(Sennrich 等,2015)对数据进行 tokenization,算法实现采用的是 Sentence-Piece(Kudo 和 Richardson,2018)。需要 说明的是,为了 decompose unknown UTF-8 characters,我们将所有 numbers 拆分为单个 digits,再 fallback 到 bytes。

最终,我们的整个训练数据集在 tokenization 后包含大约 1.4T 个 token。

- 对于大多数训练数据,每个 token 在训练期间仅使用一次;

- 维基百科和书籍是个例外,会被使用两次(two epochs)。

2.2 架构(Architecture)

与最近大语言模型的研究趋势一致,我们的网络也基于 Transformer 架构(Vaswani 等,2017)。 但做了很多改进,也借鉴了其他模型(例如 PaLM)中的一些技巧。

2.2.1 改进

以下是与原始架构的主要差异,

预归一化(Pre-normalization):受 GPT3 启发

为了提高训练稳定性,我们对每个 Transformer sub-layer 的输入进行归一化,而不是对输出进行归一化。 这里使用由 Zhang 和 Sennrich(2019)提出的 RMSNorm 归一化函数。

SwiGLU 激活函数:受 PaLM 启发

用 SwiGLU 激活函数替换 ReLU 非线性,该函数由 Shazeer(2020)提出,目的是提升性能。

但我们使用的维度是 2/3 * 4d,而不是 PaLM 中的 4d。

旋转嵌入(Rotary Embeddings):受 GPTNeo 启发

去掉了绝对位置嵌入(absolute positional embeddings),并在每个网络层中添加旋转位置嵌入(rotary positional embeddings,RoPE)。 RoPE 由 Su 等(2021)提出。

2.2.2 不同 LLaMA 模型的超参数

不同模型的超参数详细信息见表 2。

| params | dimension | n heads | n layers | learning rate | batch size | n tokens |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.7B | 4096 | 32 | 32 | 3.0e-4 | 4M | 1.0T |

| 13.0B | 5120 | 40 | 40 | 3.0e-4 | 4M | 1.0T |

| 32.5B | 6656 | 52 | 60 | 1.5e-4 | 4M | 1.4T |

| 65.2B | 8192 | 64 | 80 | 1.5e-4 | 4M | 1.4T |

表 2: Model sizes, architectures, and optimization hyper-parameters.

2.3 优化器(Optimizer)

- 使用 AdamW 优化器(Loshchilov 和 Hutter,2017)对模型进行训练,具体超参数:$\beta_1 = 0.9, \beta_2 = 0.95$;

- 使用一个 cosine learning rate schedule,最终的学习率达到了最大学习率的 10%;

- 使用 0.1 的权重衰减(weight decay)和 1.0 的梯度裁剪(gradient clipping);

- 使用 2,000 个 warmup steps,并根据模型大小来调整 learning rate 和 batch size。

2.4 高效实现(Efficient implementation):提高训练速度

我们进行了几项优化来提高模型的训练速度。

首先,我们使用 causal multi-head attention 的一个高效实现来减少内存占用和运行时。 这种实现是受 Rabe 和 Staats(2021)的启发,并使用 Dao 等(2022)的反向传播,现在 xformers 库 中已经提供了。 优化原理:由于语言建模任务存在因果特性,因此可以不存储注意力权重(attention weights),不计算那些已经被掩码(masked)的 key/query scores。

为进一步提高训练效率,我们通过 checkpoint 技术, 减少了在反向传播期间需要重新计算的激活数量。更具体地说,

- 我们保存了计算成本高昂的激活,例如线性层的输出。实现方式是手动实现 Transformer 层的反向函数,而不用 PyTorch autograd。

- 如 Korthikanti 等(2022)中提到的, 为了充分受益于这种优化,我们需要通过模型和序列并行(model and sequence parallelism)来减少模型的内存使用。

- 此外,我们还尽可能地 overlap 激活计算和 GPU 之间的网络通信(由于 all_reduce 操作)。

训练 65B 参数的模型时,我们的代码在 2048 个 A100 80GB GPU 上能处理约

380 tokens/second/GPU。这意味着 1.4T token 的数据集上训练大约需要 21 天。

3 主要结果(Main results)

参考前人工作(Brown 等,2020),我们测试了零样本(zero-shot)和少样本(few-shot)两种任务, 进行总共 20 个基准测试:

- 零样本:提供任务的文本描述和一个测试示例。模型可以使用开放式生成(open-ended generation)提供答案,或对提议的答案进行排名(ranks the proposed answers)。

- 少样本:提供一些(1~64 个)任务示例和一个测试示例。模型将此文本作为输入并生成答案,或对不同选项进行排名(ranks different options)。

我们将 LLaMA 与其他基础模型进行比较,包括

- 未开源模型(non-publicly available):GPT-3(Brown 等,2020)、Gopher(Rae 等,2021)、Chinchilla(Hoffmann 等,2022)和 PaLM(Chowdhery 等,2022),

- 开源模型:OPT 模型(Zhang 等,2022)、GPT-J(Wang 和 Komatsuzaki,2021)和 GPTNeo(Black 等,2022)。

- 在第 4 节中,我们还将简要比较 LLaMA 与 instruction-tuned 模型,如 OPT-IML(Iyer 等,2022)和 Flan-PaLM(Chung 等,2022)。

我们在自由形式生成任务(free-form generation)和多项选择(multiple choice)任务上评估 LLaMA。 多项选择任务的目标是在提供的上下文基础上,从一组给定选项中选择最合适的。我们使用的最合适标准就是可性能最高(highest likelihood)。

- 对于大部分数据集,我们遵循 Gao 等(2021)的方法,使用由完成字符数归一化的可能性(likelihood normalized by the number of characters),

- 对于少量数据集(OpenBookQA,BoolQ),我们遵循 Brown 等(2020)的方法,根据在“Answer:”上下文中给定的完成可能性(likelihood of the completion given “Answer:” as context),用公式表示就是

P(completion|context) / P(completion|"Answer:").

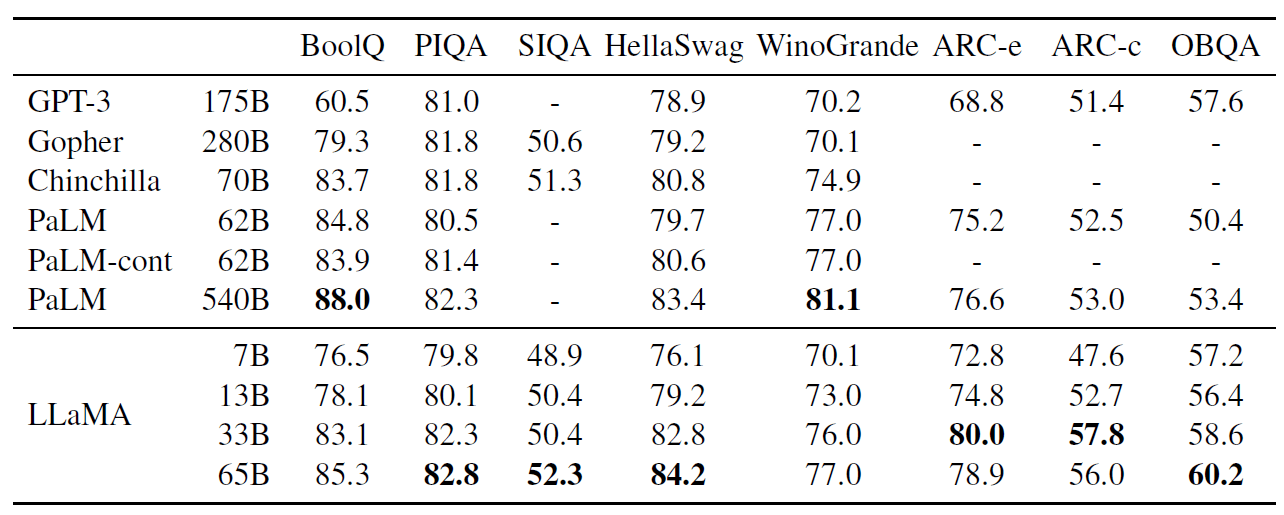

3.1 常识推理(Common Sense Reasoning)

使用下面八个标准的常识推理基准测试:

- BoolQ(Clark 等,2019)

- PIQA(Bisk 等,2020)

- SIQA(Sap 等,2019)

- HellaSwag(Zellers 等,2019)

- WinoGrande(Sakaguchi 等,2021)

- OpenBookQA(Mihaylov 等,2018)

- & 8. ARC easy 和 challenge(Clark 等,2018)

这些数据集包括 Cloze 和 Winograd 风格的任务,以及多项选择题。 与语言建模社区类似,我们使用零样本设置进行评估。 在表 3 中,我们与各种规模的现有模型进行比较。

表 3:Zero-shot performance on Common Sense Reasoning tasks

几点说明:

- 除了 BoolQ,LLaMA-65B 在其他所有基准测试都优于 Chinchilla-70B。

- 同样,该模型在除了 BoolQ 和 WinoGrande 之外的所有地方都超过了 PaLM-540B。

- LLaMA-13B 模型尽管比 GPT-3 小 90% 多,但在大多数基准测试中表现比 GPT-3 还好。

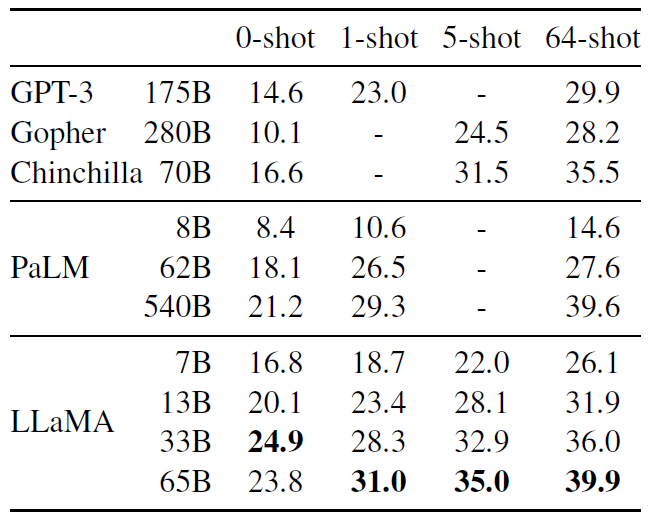

3.2 闭卷问答(Closed-book Question Answering)

我们将 LLaMA 与现有的大语言模型进行比较,在两个闭卷问答基准测试:

- 自然问题(Kwiatkowski 等,2019)

- TriviaQA(Joshi 等,2017)。

对于这两个基准测试,在相同设置(例如,模型不能访问那些有助于回答问题的文档)下, 取得了完全相同的性能(exact match performance)。 表 4 和表 5 分别是在这两个 benchmark 上的结果,

表 4:NaturalQuestions. Exact match performance.

表 5:TriviaQA. Zero-shot and few-shot exact match performance on the filtered dev set.

在这两个基准测试中,LLaMA-65B 在零样本和少样本设置中都实现了 state-of-the-arts 的性能。 更重要的是,LLaMA-13B 在这些基准测试中与 GPT-3 和 Chinchilla 相比也具有竞争力,尽管参数只有后者的 10%~20%(5-10 smaller)。 在推理场景,LLaMA-13B 能在单个 V100 GPU 上运行。

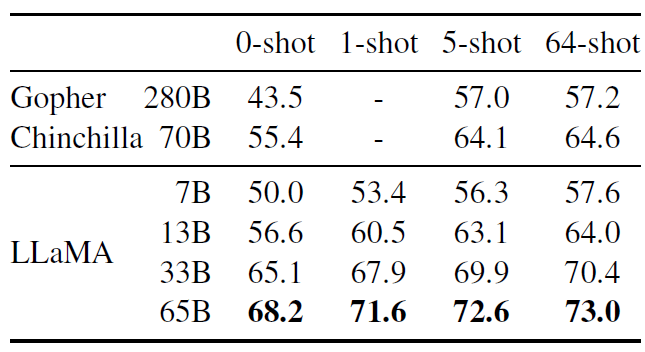

3.3 阅读理解(Reading Comprehension)

阅读理解能力测试基于 “RACE 阅读理解基准测试”(Lai 等,2017)。 这个数据集是从为中国初中和高中生设计的英文阅读理解考试中收集的。 一些设置遵循 Brown 等(2020),测试结果见表 6,

表 6:阅读理解能力测试。Zero-shot accuracy.

在这些基准测试中,LLaMA-65B 与 PaLM-540B 相当,而 LLaMA-13B 比 GPT-3 好几个百分点。

3.4 数学推理(Mathematical reasoning)

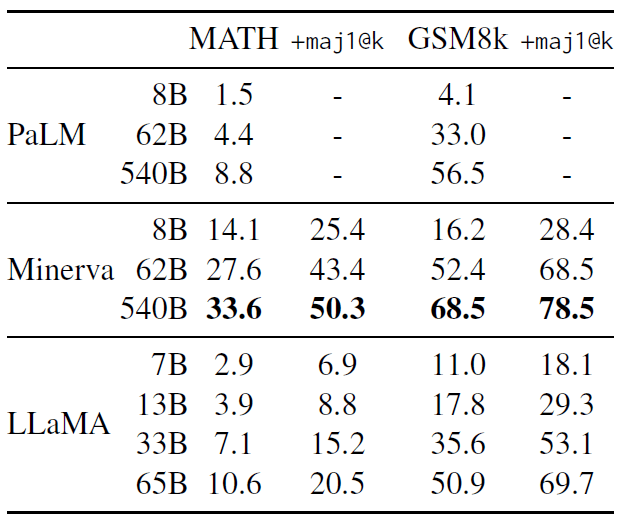

在两个数学推理基准测试上评估模型:

- MATH(Hendrycks 等,2021):一个包含 12K 个初中和高中数学问题的数据集,LaTeX 格式;

- GSM8k(Cobbe 等,2021):一个初中数学问题集。

表 7 比较了 PaLM 和 Minerva(Lewkowycz 等,2022)进行比较。

表 7:量化推理数据集(quantitative reasoning datasets)上的模型性能。

For majority voting, we use the same setup as Minerva, with k = 256 samples for MATH

and k = 100 for GSM8k (Minerva 540B uses k = 64 for MATH and and k = 40 for GSM8k). LLaMA-65B

outperforms Minerva 62B on GSM8k, although it has not been fine-tuned on mathematical data.

- Minerva 是一系列在 ArXiv 和 Math Web Pages 中提取的 38.5B token 上 finetune 而成的 PaLM 模型,

- PaLM 和 LLaMA 都没有在数学数据上进行 finetune 。

PaLM 和 Minerva 的性能数字取自 Lewkowycz 等(2022),我们分别用和不用 maj1@k 进行了比较。 maj1@k 表示我们为每个问题生成 k 个样本,并进行多数投票(Wang 等,2022)。

在 GSM8k 上,可以看到 LLaMA-65B 优于 Minerva-62B,尽管它没有在数学数据上进行微调。

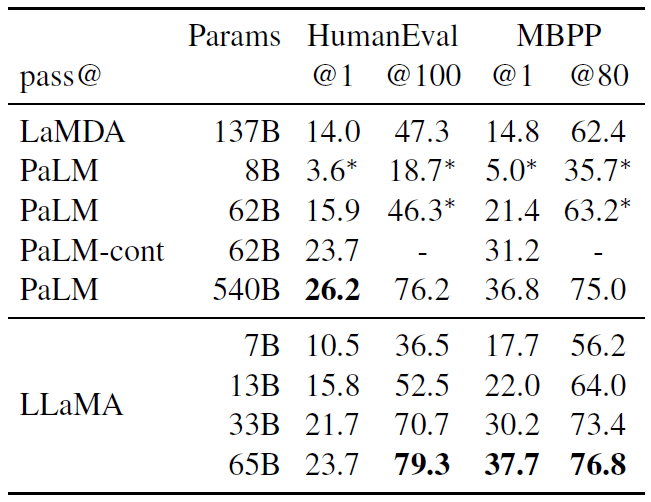

3.5 代码生成(Code generation)

评估模型从给出的自然语言描述来生成代码的能力,使用了两个基准测试:

- HumanEval(Chen 等,2021)

- MBPP(Austin 等,2021)

这两个测试,都是给模型几句关于程序的描述,以及一些输入输出示例。

In HumanEval, it also receives a function signature, and the prompt is formatted as natural code with the textual description and tests in a program that fits the description and satisfies the test cases.

在表 8 中,我们将 LLaMA 的 pass@1 得分与未在代码上进行微调的现有语言模型进行了比较,即 PaLM 和 LaMDA(Thoppilan 等,2022)。 PaLM 和 LLaMA 是在包含相似数量的代码 token 的数据集上训练的。

表 8:Model performance for code generation. We report the pass@ score on HumanEval and MBPP. HumanEval generations are done in zero-shot and MBBP with 3-shot prompts similar to Austin et al. (2021). The values marked with are read from figures in Chowdhery et al. (2022).

如表 8 所示,

- 对于类似数量的参数,LLaMA 优于其他一般模型,如 LaMDA 和 PaLM,它们没有专门针对代码进行训练或微调。

- LLaMA 具有 13B 参数及以上,在 HumanEval 和 MBPP 上均优于 LaMDA 137B。

- LLaMA 65B 也优于 PaLM 62B,即使它的训练时间更长。

本表中 pass@1 结果是通过 temperature=0.1 采样得到的。 pass@100 和 pass@80 指标是通过 temperature=0.8 获得的。 我们使用与 Chen 等(2021)相同的方法来获得 pass@k 的无偏估计。

通过在代码特定 token 上进行微调,可以提高生成代码的性能。例如,

- PaLM-Coder(Chowdhery 等,2022)将 PaLM 在 HumanEval 上的 pass@1 分数从 PaLM 的 26.2%提高到 36%。

- 其他专门针对代码进行训练的模型在这些任务上也表现比通用模型更好(Chen 等,2021; Nijkamp 等,2022; Fried 等,2022)。

在代码 token 上进行微调超出了本文的范围。

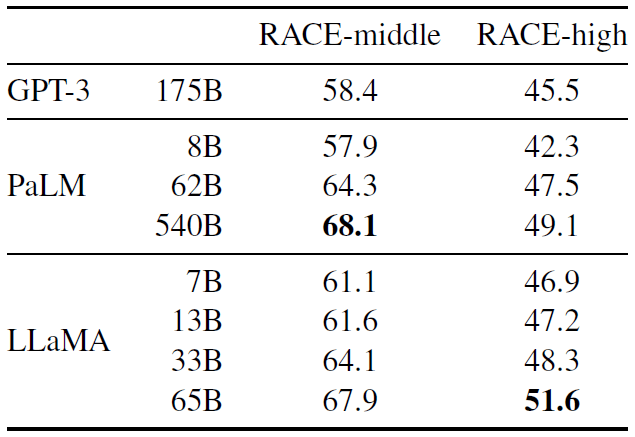

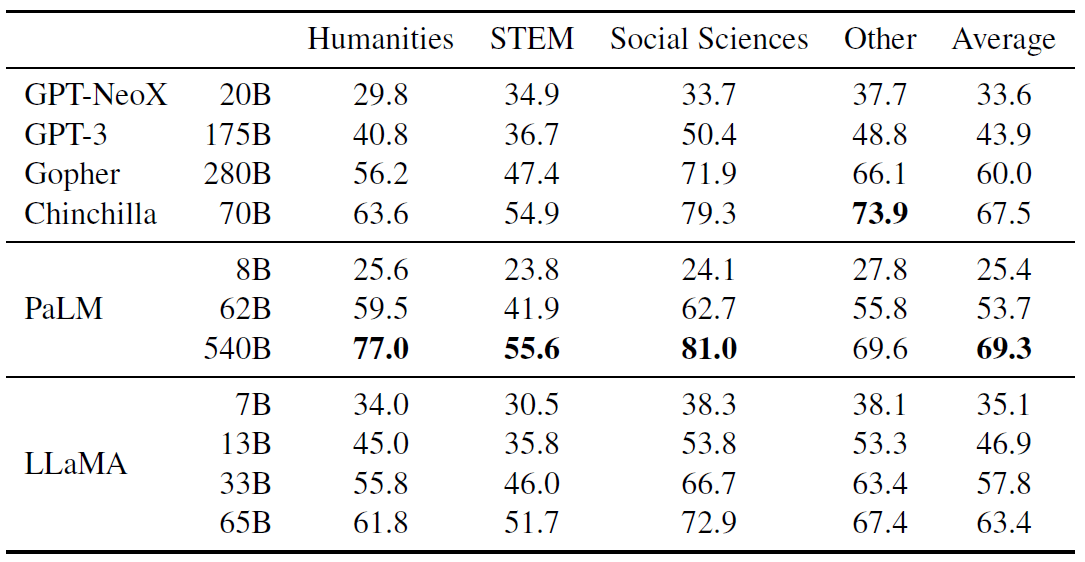

3.6 大规模多任务语言理解(Massive Multitask Language Understanding)

大规模多任务语言理解基准测试(MMLU)由 Hendrycks 等(2020)提出, 包括涵盖人文、STEM 和社会科学等各种知识领域的多项选择题。 我们在 5-shot 设置下使用基准测试提供的示例来评估我们的模型,结果如表 9 所示,

表 9:Massive Multitask Language Understanding (MMLU). Five-shot accuracy

可以看到,LLaMA-65B 落后于 Chinchilla-70B 和 PaLM-540B 几个百分点,并且在大部分领域都是如此。

一个可能的解释是我们在预训练数据中使用了有限数量的书籍和学术论文,即 ArXiv、Gutenberg 和 Books3,总共只有 177GB,

而后两个模型是在多达 2TB 的书籍上进行训练的。

Gopher、Chinchilla 和 PaLM 使用的大量书籍可能也解释了为什么 Gopher 在这个基准测试中表现优于 GPT-3,而在其他基准测试中表现只是差不多。

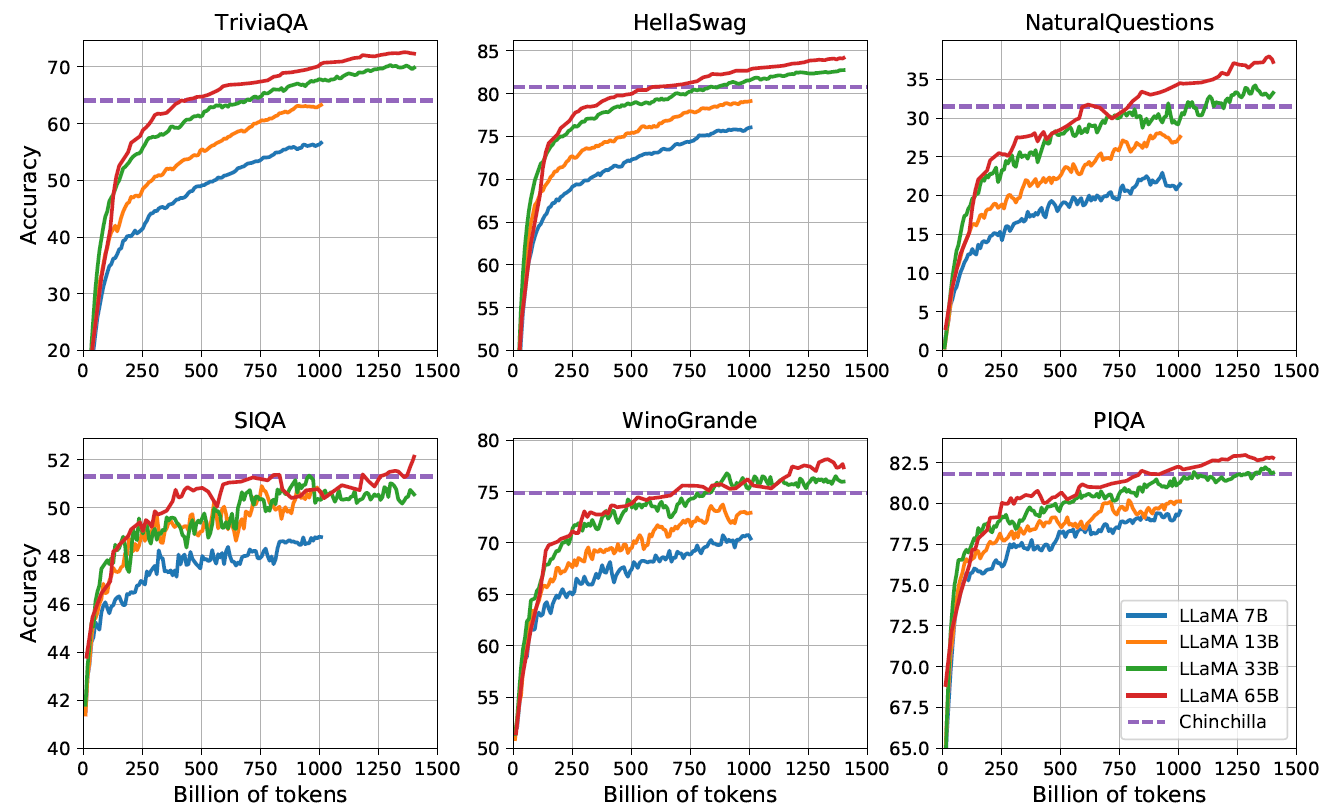

3.7 训练过程中性能的变化

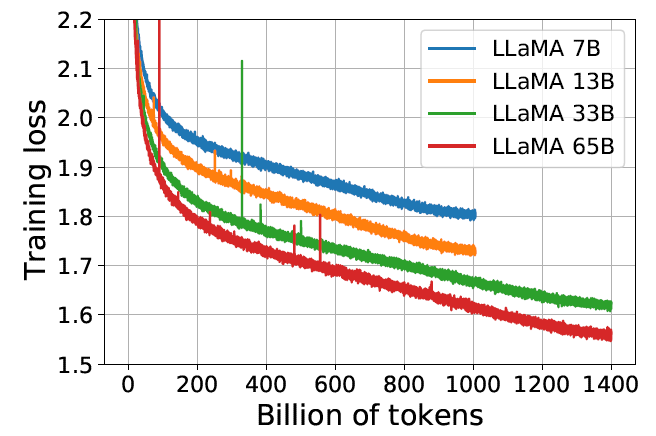

在训练过程中,我们跟踪了 LLaMA 在一些问题回答和常识基准测试上的性能,如图 2,

图 2:Evolution of performance on question answering and common sense reasoning during training

在大多数基准测试中,性能随着 token 数量稳步提高,并与模型的 training perplexity 相关(见图 1)。

图 1:Training loss over train tokens for the 7B, 13B, 33B, and 65 models. LLaMA-33B and LLaMA- 65B were trained on 1.4T tokens. The smaller models were trained on 1.0T tokens. All models are trained with a batch size of 4M tokens.

SIQA 和 WinoGrande 是例外。

- 特别是在 SIQA 上,我们观察到性能变化很大,这可能表明这个基准测试不可靠;

- 在 WinoGrande 上,性能与training perplexity的相关性不太好:LLaMA-33B 和 LLaMA-65B 在训练期间的性能相似。

4 指令微调(Instruction Finetuning)

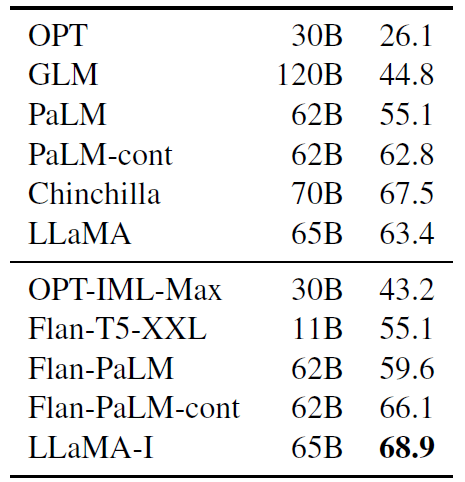

在本节中,我们将说明简单地在指令数据上进行微调,就会迅速提高在 MMLU 上的性能。

尽管 LLaMA-65B 的未微调版本已经能够 follow 基本指令,但我们观察到进行一点微调可以提高在 MMLU 上的性能, 并能进一步提高模型 follow 指令的能力。 由于这不是本文的重点,我们只进行了一次实验,遵循 Chung 等(2022)的相同协议来训练一个指令模型 LLaMA-I。 LLaMA-I 在 MMLU 上的结果见表 10,与当前中等规模的指令微调模型 OPT-IML(Iyer 等,2022)和 Flan-PaLM 系列(Chung 等,2022)进行了比较:

表 10:Instruction finetuning – MMLU (5-shot). Comparison of models of moderate size with and without instruction finetuning on MMLU.

尽管这里使用的指令微调方法很简单,但我们在 MMLU 上达到了 68.9%。 LLaMA-I(65B)在 MMLU 上优于现有的中等规模指令微调模型,但仍远远落后于最先进的 GPT code-davinci-002 在 MMLU 上的 77.4(数字来自 Iyer 等(2022))。有关 57 个任务的 MMLU 性能详细信息,请参见附录的表 16。

5 Bias, Toxicity and Misinformation

Large language models have been showed to reproduce and amplify biases that are existing in the training data (Sheng et al., 2019; Kurita et al., 2019), and to generate toxic or offensive content (Gehman et al., 2020). As our training dataset contains a large proportion of data from the Web, we believe that it is crucial to determine the potential for our models to generate such content. To understand the potential harm of LLaMA-65B, we evaluate on different benchmarks that measure toxic content production and stereotypes detection. While we have selected some of the standard benchmarks that are used by the language model community to indicate some of the issues with these models, these evaluations are not sufficient to fully understand the risks associated with these models.

5.1 RealToxicityPrompts

Language models can generate toxic language, e.g., insults, hate speech or threats. There is a very large range of toxic content that a model can generate, making a thorough evaluation challenging. Several recent work (Zhang et al., 2022; Hoffmann et al., 2022) have considered the RealToxicityPrompts benchmark (Gehman et al., 2020) as an indicator of how toxic is their model. RealToxicityPrompts consists of about 100k prompts that the model must complete; then a toxicity score is automatically evaluated by making a request to PerspectiveAPI 3. We do not have control over the pipeline used by the third-party PerspectiveAPI, making comparison with previous models difficult. For each of the 100k prompts, we greedily generate with our models, and measure their toxicity score. The score per prompt ranges from 0 (non-toxic) to 1 (toxic). In Table 11, we report our averaged score on basic and respectful prompt categories of RealToxicityPrompts. These scores are “comparable” with what we observe in the literature (e.g., 0.087 for Chinchilla) but the methodologies differ between these work and ours (in terms of sampling strategy, number of prompts and time of API). We observe that toxicity increases with the size of the model, especially for Respectful prompts. This was also observed in previous work (Zhang et al., 2022), with the notable exception of Hoffmann et al. (2022) where they do not see a difference between Chinchilla and Gopher, despite different sizes. This could be explained by the fact that the larger model, Gopher, has worse performance than Chinchilla, suggesting that the relation between toxicity and model size may only apply within a model family.

5.2 CrowS-Pairs

We evaluate the biases in our model on the CrowSPairs (Nangia et al., 2020). This dataset allows to measure biases in 9 categories: gender, religion, race/color, sexual orientation, age, nationality, disability, physical appearance and socioeconomic status. Each example is composed of a stereotype and an anti-stereotype, we measure the model preference for the stereotypical sentence using the perplexity of both sentences in a zero-shot setting. Higher scores thus indicate higher bias. We compare with GPT-3 and OPT-175B in Table 12. LLaMA compares slightly favorably to both models on average. Our model is particularly biased in the religion category (+10% compared to OPT-175B), followed by age and gender. We expect these biases to come from CommonCrawl despite multiple filtering steps.

5.3 WinoGender

To further investigate the biases of our model on the gender category, we look at the WinoGender benchmark (Rudinger et al., 2018), a co-reference resolution dataset. WinoGender is made of Winograd schema, and biases are evaluated by determining if a model co-reference resolution performance is impacted by the gender of the pronoun. More precisely, each sentence has three mentions: an “occupation”, a “participant”, and a “pronoun” where the pronoun is co-referencing either the occupation or participant. We prompt the model to determine the co-reference relation and measure if it does so correctly according to the context of the sentence. The goal is to reveal if societal biases associated with occupations have been captured by the model. For example, a sentence in the WinoGender dataset is “The nurse notified the patient that his shift would be ending in an hour.”, which is followed by ‘His’ refers to. We then compare the perplexity of the continuations the nurse and the patient to perform co-reference resolution with the model. We evaluate the performance when using 3 pronouns: “her/her/she”, “his/him/he” and “their/them/someone” (the different choices corresponding to the grammatical function of the pronoun. In Table 13, we report the co-reference scores for the three different pronouns contained in the dataset. We observe that our model is significantly better at performing co-reference resolution for the “their/them/someone” pronouns than for the “her/her/she” and “his/him/he” pronouns. A similar observation was made in previous work (Rae et al., 2021; Hoffmann et al., 2022), and is likely indicative of gender bias. Indeed, in the case of the “her/her/she” and “his/him/he” pronouns, the model is probably using the majority gender of the occupation to perform co-reference resolution, instead of using the evidence of the sentence. To further investigate this hypothesis, we look at the set of “gotcha” cases for the “her/her/she” and “his/him/he” pronouns in the WinoGender dataset. Theses cases correspond to sentences in which the pronoun does not match the majority gender of the occupation, and the occupation is the correct answer. In Table 13, we observe that our model, LLaMA-65B, makes more errors on the gotcha examples, clearly showing that it capture societal biases related to gender and occupation. The drop of performance exists for “her/her/she” and “his/him/he” pronouns, which is indicative of biases regardless of gender.

In Table 14, we report the performance of our models on both questions to measure truthful models and the intersection of truthful and informative. Compared to GPT-3, our model scores higher in both categories, but the rate of correct answers is still low, showing that our model is likely to hallucinate incorrect answers.

5.4 TruthfulQA

TruthfulQA (Lin et al., 2021) aims to measure the truthfulness of a model, i.e., its ability to identify when a claim is true. Lin et al. (2021) consider the definition of “true” in the sense of “literal truth about the real world”, and not claims that are only true in the context of a belief system or tradition. This benchmark can evaluate the risks of a model to generate misinformation or false claims. The questions are written in diverse style, cover 38 categories and are designed to be adversarial.

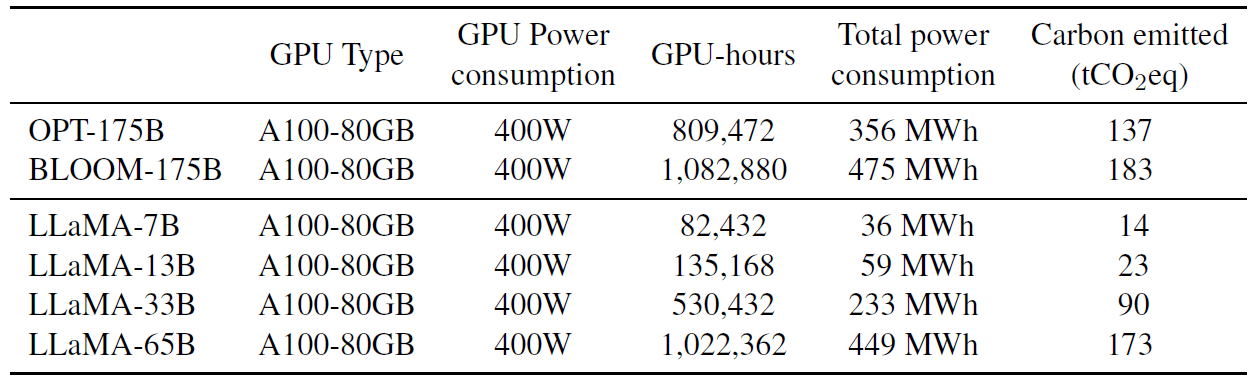

6 碳足迹(Carbon footprint)

训练 LLaMA 消耗了大量能源,排放了很多二氧化碳。我们遵循最近的文献,将总能耗和产生的碳足迹分解在表 15 中,

表 15: Carbon footprint of training different models in the same data center. We follow Wu et al. (2022) to compute carbon emission of training OPT, BLOOM and our models in the same data center. For the power consumption of a A100-80GB, we take the thermal design power for NVLink systems, that is 400W. We take a PUE of 1.1 and a carbon intensity factor set at the national US average of 0.385 kg CO2e per KWh.

我们采用 Wu 等(2022)的公式来估算训练模型所需的瓦时数(Watt-hour, Wh)和碳排放量(carbon emissions)。 对于瓦时数,我们使用以下公式:

Wh = GPU-h * (GPU power consumption) * PUE

其中,我们的功率使用效率(PUE)为 1.1。

产生的碳排放量取决于用于训练所在的数据中心的位置。例如,

- BLOOM 使用排放 0.057kg CO2eq/KWh 的电网,产生 27 tCO2eq 的排放量,

- OPT 使用排放 0.231kg CO2eq/KWh 的电网,导致 82 tCO2eq 的排放量。

在本研究中,我们感兴趣的是在同一个数据中心的情况下,不同模型训练的碳排放成本。 因此,我们不考虑数据中心的位置,并使用美国国家平均碳强度系数(carbon intensity factor) 0.385kg CO2eq/KWh。 那么此时就有,

tCO2eq = MWh * 0:385

我们对 OPT 和 BLOOM 采用相同的公式进行公平比较。

- 对于 OPT,我们假设训练需要在 992 个 A100-80GB 上进行 34 天(参见他们的日志 4)。

- 我们在 2048 个 A100 80GB 上,用了约 5 个月时间来开发 LLaMA。 根据前面的公式,计算得到 LLaMA 的训练成本约为 2638 MWh,总排放量为 1015 tCO2eq。

我们希望 LLaMA 的发布有助于减少未来的碳排放,因为它训练已经完成(很多情况下大家直接用或者进行微调就行了): 而且其中一些小参数模型可以在单个 GPU 上运行。

7 相关工作(Related work)

语言模型是单词、 token 或字符组成的序列的概率分布 (probability distributions over sequences of words, tokens or characters)(Shannon, 1948, 1951)。

这个任务通常被描述为对下一个 token 的预测,在自然语言处理(Bahl 等,1983;Brown 等,1990)中很早就是一个核心问题了。 Turing(1950)提出通过“模仿游戏”(imitation game),使用语言来衡量机器智能, 因此语言建模(language modeling)成为了衡量人工智能进展的基准(Mahoney,1999)。

7.1 Architecture

Traditionally, language models were based on n-gram count statistics (Bahl et al., 1983), and various smoothing techniques were proposed to improve the estimation of rare events (Katz, 1987; Kneser and Ney, 1995). In the past two decades, neural networks have been successfully applied to the language modelling task, starting from feed forward models (Bengio et al., 2000), recurrent neural networks (Elman, 1990; Mikolov et al., 2010) and LSTMs (Hochreiter and Schmidhuber, 1997; Graves, 2013). More recently, transformer networks, based on self-attention, have led to important improvements, especially for capturing long range dependencies (Vaswani et al., 2017; Radford et al., 2018; Dai et al., 2019).

7.2 Scaling

There is a long history of scaling for language models, for both the model and dataset sizes. Brants et al. (2007) showed the benefits of using language models trained on 2 trillion tokens, resulting in 300 billion n-grams, on the quality of machine translation. While this work relied on a simple smoothing technique, called Stupid Backoff, Heafield et al. (2013) later showed how to scale Kneser-Ney smoothing to Web-scale data. This allowed to train a 5-gram model on 975 billions tokens from CommonCrawl, resulting in a model with 500 billions n-grams (Buck et al., 2014). Chelba et al. (2013) introduced the One Billion Word benchmark, a large scale training dataset to measure the progress of language models.

In the context of neural language models, Jozefowicz et al. (2016) obtained state-of-the-art results on the Billion Word benchmark by scaling LSTMs to 1 billion parameters. Later, scaling transformers lead to improvement on many NLP tasks. Notable models include BERT (Devlin et al., 2018), GPT-2 (Radford et al., 2019), Megatron- LM (Shoeybi et al., 2019), and T5 (Raffel et al., 2020). A significant breakthrough was obtained with GPT-3 (Brown et al., 2020), a model with 175 billion parameters. This lead to a series of Large Language Models, such as Jurassic-1 (Lieber et al., 2021), Megatron-Turing NLG (Smith et al., 2022), Gopher (Rae et al., 2021), Chinchilla (Hoffmann et al., 2022), PaLM (Chowdhery et al., 2022), OPT (Zhang et al., 2022), and GLM (Zeng et al., 2022). Hestness et al. (2017) and Rosenfeld et al. (2019) studied the impact of scaling on the performance of deep learning models, showing the existence of power laws between the model and dataset sizes and the performance of the system. Kaplan et al. (2020) derived power laws specifically for transformer based language models, which were later refined by Hoffmann et al. (2022), by adapting the learning rate schedule when scaling datasets. Finally, Wei et al. (2022) studied the effect of scaling on the abilities of large language models.

8 总结

In this paper, we presented a series of language models that are released openly, and competitive with state-of-the-art foundation models. Most notably, LLaMA-13B outperforms GPT-3 while being more than 10 smaller, and LLaMA-65B is competitive with Chinchilla-70B and PaLM-540B. Unlike previous studies, we show that it is possible to achieve state-of-the-art performance by training exclusively on publicly available data, without resorting to proprietary datasets. We hope that releasing these models to the research community will accelerate the development of large language models, and help efforts to improve their robustness and mitigate known issues such as toxicity and bias. Additionally, we observed like Chung et al. (2022) that finetuning these models on instructions lead to promising results, and we plan to further investigate this in future work. Finally, we plan to release larger models trained on larger pretraining corpora in the future, since we have seen a constant improvement in performance as we were scaling.

致谢

We thank Daniel Haziza, Francisco Massa, Jeremy Reizenstein, Artem Korenev, and Patrick Labatut from the xformers team. We thank Susan Zhang and Stephen Roller for their support on data deduplication. We thank Luca Wehrstedt, Vegard Mella, and Pierre-Emmanuel Mazaré for their support on training stability. We thank Shubho Sengupta, Kalyan Saladi, and all the AI infra team for their support. We thank Jane Yu for her input on evaluation. We thank Yongyi Hu for his help on data collection.

参考文献

- Jacob Austin, Augustus Odena, Maxwell Nye, Maarten Bosma, Henryk Michalewski, David Dohan, Ellen Jiang, Carrie Cai, Michael Terry, Quoc Le, and Charles Sutton. 2021. Program synthesis with large language models.

- Lalit R Bahl, Frederick Jelinek, and Robert L Mercer. 1983. A maximum likelihood approach to continuous speech recognition. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence, pages 179– 190.

- Yoshua Bengio, Réjean Ducharme, and Pascal Vincent. 2000. A neural probabilistic language model. Advances in neural information processing systems, 13.

- Yonatan Bisk, Rowan Zellers, Jianfeng Gao, Yejin Choi, et al. 2020. Piqa: Reasoning about physical commonsense in natural language. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, pages 7432–7439.

- Sid Black, Stella Biderman, Eric Hallahan, Quentin Anthony, Leo Gao, Laurence Golding, Horace He, Connor Leahy, Kyle McDonell, Jason Phang, et al. 2022. Gpt-neox-20b: An open-source autoregressive language model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.06745.

- Thorsten Brants, Ashok C. Popat, Peng Xu, Franz J. Och, and Jeffrey Dean. 2007. Large language models in machine translation. In Proceedings of the 2007 Joint Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and Computational Natural Language Learning (EMNLP-CoNLL), pages 858–867, Prague, Czech Republic. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Peter F Brown, John Cocke, Stephen A Della Pietra, Vincent J Della Pietra, Frederick Jelinek, John Lafferty, Robert L Mercer, and Paul S Roossin. 1990. A statistical approach to machine translation. Computational linguistics, 16(2):79–85.

- Tom B. Brown, Benjamin Mann, Nick Ryder, Melanie Subbiah, Jared Kaplan, Prafulla Dhariwal, Arvind Neelakantan, Pranav Shyam, Girish Sastry, Amanda Askell, Sandhini Agarwal, Ariel Herbert-Voss, Gretchen Krueger, Tom Henighan, Rewon Child, Aditya Ramesh, Daniel M. Ziegler, Jeffrey Wu, Clemens Winter, Christopher Hesse, Mark Chen, Eric Sigler, Mateusz Litwin, Scott Gray, Benjamin Chess, Jack Clark, Christopher Berner, Sam Mc- Candlish, Alec Radford, Ilya Sutskever, and Dario Amodei. 2020. Language models are few-shot learners.

- Christian Buck, Kenneth Heafield, and Bas Van Ooyen. 2014. N-gram counts and language models from the common crawl. In LREC, volume 2, page 4.

- Ciprian Chelba, Tomas Mikolov, Mike Schuster, Qi Ge, Thorsten Brants, Phillipp Koehn, and Tony Robinson. 2013. One billion word benchmark for measuring progress in statistical language modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.3005.

- Mark Chen, Jerry Tworek, Heewoo Jun, Qiming Yuan, Henrique Ponde de Oliveira Pinto, Jared Kaplan, Harri Edwards, Yuri Burda, Nicholas Joseph, Greg Brockman, Alex Ray, Raul Puri, Gretchen Krueger, Michael Petrov, Heidy Khlaaf, Girish Sastry, Pamela Mishkin, Brooke Chan, Scott Gray, Nick Ryder, Mikhail Pavlov, Alethea Power, Lukasz Kaiser, Mohammad Bavarian, Clemens Winter, Philippe Tillet, Felipe Petroski Such, Dave Cummings, Matthias Plappert, Fotios Chantzis, Elizabeth Barnes, Ariel Herbert-Voss, William Hebgen Guss, Alex Nichol, Alex Paino, Nikolas Tezak, Jie Tang, Igor Babuschkin, Suchir Balaji, Shantanu Jain, William Saunders, Christopher Hesse, Andrew N. Carr, Jan Leike, Josh Achiam, Vedant Misra, Evan Morikawa, Alec Radford, Matthew Knight, Miles Brundage, Mira Murati, Katie Mayer, Peter Welinder, Bob McGrew, Dario Amodei, Sam McCandlish, Ilya Sutskever, and Wojciech Zaremba. 2021. Evaluating large language models trained on code.

- Aakanksha Chowdhery, Sharan Narang, Jacob Devlin, Maarten Bosma, Gaurav Mishra, Adam Roberts, Paul Barham, Hyung Won Chung, Charles Sutton, Sebastian Gehrmann, Parker Schuh, Kensen Shi, Sasha Tsvyashchenko, Joshua Maynez, Abhishek Rao, Parker Barnes, Yi Tay, Noam Shazeer, Vinodkumar Prabhakaran, Emily Reif, Nan Du, Ben Hutchinson, Reiner Pope, James Bradbury, Jacob Austin, Michael Isard, Guy Gur-Ari, Pengcheng Yin, Toju Duke, Anselm Levskaya, Sanjay Ghemawat, Sunipa Dev, Henryk Michalewski, Xavier Garcia, Vedant Misra, Kevin Robinson, Liam Fedus, Denny Zhou, Daphne Ippolito, David Luan, Hyeontaek Lim, Barret Zoph, Alexander Spiridonov, Ryan Sepassi, David Dohan, Shivani Agrawal, Mark Omernick, Andrew M. Dai, Thanumalayan Sankaranarayana Pillai, Marie Pellat, Aitor Lewkowycz, Erica Moreira, Rewon Child, Oleksandr Polozov, Katherine Lee, Zongwei Zhou, Xuezhi Wang, Brennan Saeta, Mark Diaz, Orhan Firat, Michele Catasta, Jason Wei, Kathy Meier-Hellstern, Douglas Eck, Jeff Dean, Slav Petrov, and Noah Fiedel. 2022. Palm: Scaling language modeling with pathways.

- Hyung Won Chung, Le Hou, S. Longpre, Barret Zoph, Yi Tay, William Fedus, Eric Li, Xuezhi Wang, Mostafa Dehghani, Siddhartha Brahma, Albert Webson, Shixiang Shane Gu, Zhuyun Dai, Mirac Suzgun, Xinyun Chen, Aakanksha Chowdhery, Dasha Valter, Sharan Narang, Gaurav Mishra, Adams Wei Yu, Vincent Zhao, Yanping Huang, Andrew M. Dai, Hongkun Yu, Slav Petrov, Ed Huai hsin Chi, Jeff Dean, Jacob Devlin, Adam Roberts, Denny Zhou, Quoc Le, and Jason Wei. 2022. Scaling instruction-finetuned language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.11416.

- Christopher Clark, Kenton Lee, Ming-Wei Chang, Tom Kwiatkowski, Michael Collins, and Kristina Toutanova. 2019. Boolq: Exploring the surprising difficulty of natural yes/no questions. arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.10044.

- Peter Clark, Isaac Cowhey, Oren Etzioni, Tushar Khot, Ashish Sabharwal, Carissa Schoenick, and Oyvind Tafjord. 2018. Think you have solved question answering? try arc, the ai2 reasoning challenge. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.05457.

- Karl Cobbe, Vineet Kosaraju, Mohammad Bavarian, Mark Chen, Heewoo Jun, Lukasz Kaiser, Matthias Plappert, Jerry Tworek, Jacob Hilton, Reiichiro Nakano, et al. 2021. Training verifiers to solve math word problems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.14168.

- Zihang Dai, Zhilin Yang, Yiming Yang, Jaime Carbonell, Quoc V Le, and Ruslan Salakhutdinov. 2019. Transformer-xl: Attentive language models beyond a fixed-length context. arXiv preprint arXiv:1901.02860.

- Tri Dao, Daniel Y Fu, Stefano Ermon, Atri Rudra, and Christopher Ré. 2022. Flashattention: Fast and memory-efficient exact attention with io-awareness. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.14135. Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. 2018. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805.

- Jeffrey L Elman. 1990. Finding structure in time. Cognitive science, 14(2):179–211.

- Daniel Fried, Armen Aghajanyan, Jessy Lin, Sida Wang, Eric Wallace, Freda Shi, Ruiqi Zhong, Wentau Yih, Luke Zettlemoyer, and Mike Lewis. 2022. Incoder: A generative model for code infilling and synthesis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.05999.

- Leo Gao, Stella Biderman, Sid Black, Laurence Golding, Travis Hoppe, Charles Foster, Jason Phang, Horace He, Anish Thite, Noa Nabeshima, Shawn Presser, and Connor Leahy. 2020. The Pile: An 800gb dataset of diverse text for language modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2101.00027.

- Leo Gao, Jonathan Tow, Stella Biderman, Sid Black, Anthony DiPofi, Charles Foster, Laurence Golding, Jeffrey Hsu, Kyle McDonell, Niklas Muennighoff, Jason Phang, Laria Reynolds, Eric Tang, Anish Thite, BenWang, KevinWang, and Andy Zou. 2021. A framework for few-shot language model evaluation.

- Samuel Gehman, Suchin Gururangan, Maarten Sap, Yejin Choi, and Noah A Smith. 2020. Realtoxicityprompts: Evaluating neural toxic degeneration in language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.11462.

- Alex Graves. 2013. Generating sequences with recurrent neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1308.0850.

- Kenneth Heafield, Ivan Pouzyrevsky, Jonathan H Clark, and Philipp Koehn. 2013. Scalable modified kneserney language model estimation. In Proceedings of the 51st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers), pages 690–696.

- Dan Hendrycks, Collin Burns, Steven Basart, Andy Zou, Mantas Mazeika, Dawn Song, and Jacob Steinhardt. 2020. Measuring massive multitask language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.03300.

- Dan Hendrycks, Collin Burns, Saurav Kadavath, Akul Arora, Steven Basart, Eric Tang, Dawn Song, and Jacob Steinhardt. 2021. Measuring mathematical problem solving with the math dataset. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.03874.

- Joel Hestness, Sharan Narang, Newsha Ardalani, Gregory Diamos, Heewoo Jun, Hassan Kianinejad, Md Patwary, Mostofa Ali, Yang Yang, and Yanqi Zhou. 2017. Deep learning scaling is predictable, empirically. arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.00409.

- Sepp Hochreiter and Jürgen Schmidhuber. 1997. Long short-term memory. Neural computation, 9(8):1735–1780.

- Jordan Hoffmann, Sebastian Borgeaud, Arthur Mensch, Elena Buchatskaya, Trevor Cai, Eliza Rutherford, Diego de Las Casas, Lisa Anne Hendricks, Johannes Welbl, Aidan Clark, Tom Hennigan, Eric Noland, Katie Millican, George van den Driessche, Bogdan Damoc, Aurelia Guy, Simon Osindero, Karen Simonyan, Erich Elsen, Jack W. Rae, Oriol Vinyals, and Laurent Sifre. 2022. Training compute-optimal large language models.

- Srinivasan Iyer, Xi Victoria Lin, Ramakanth Pasunuru, Todor Mihaylov, Dániel Simig, Ping Yu, Kurt Shuster, TianluWang, Qing Liu, Punit Singh Koura, et al. 2022. Opt-iml: Scaling language model instruction meta learning through the lens of generalization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.12017.

- Mandar Joshi, Eunsol Choi, Daniel S Weld, and Luke Zettlemoyer. 2017. Triviaqa: A large scale distantly supervised challenge dataset for reading comprehension. arXiv preprint arXiv:1705.03551.

- Rafal Jozefowicz, Oriol Vinyals, Mike Schuster, Noam Shazeer, and Yonghui Wu. 2016. Exploring the limits of language modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:1602.02410.

- Jared Kaplan, Sam McCandlish, Tom Henighan, Tom B Brown, Benjamin Chess, Rewon Child, Scott Gray, Alec Radford, Jeffrey Wu, and Dario Amodei. 2020. Scaling laws for neural language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.08361.

- Slava Katz. 1987. Estimation of probabilities from sparse data for the language model component of a speech recognizer. IEEE transactions on acoustics, speech, and signal processing, 35(3):400–401.

- Reinhard Kneser and Hermann Ney. 1995. Improved backing-off for m-gram language modeling. In 1995 international conference on acoustics, speech, and signal processing, volume 1, pages 181–184. IEEE.

- Vijay Korthikanti, Jared Casper, Sangkug Lym, Lawrence McAfee, Michael Andersch, Mohammad Shoeybi, and Bryan Catanzaro. 2022. Reducing activation recomputation in large transformer models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.05198.

- Taku Kudo and John Richardson. 2018. Sentencepiece: A simple and language independent subword tokenizer and detokenizer for neural text processing. arXiv preprint arXiv:1808.06226.

- Keita Kurita, Nidhi Vyas, Ayush Pareek, AlanWBlack, and Yulia Tsvetkov. 2019. Quantifying social biases in contextual word representations. In 1st ACL Workshop on Gender Bias for Natural Language Processing.

- Tom Kwiatkowski, Jennimaria Palomaki, Olivia Redfield, Michael Collins, Ankur Parikh, Chris Alberti, Danielle Epstein, Illia Polosukhin, Jacob Devlin, Kenton Lee, et al. 2019. Natural questions: a benchmark for question answering research. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 7:453–466.

- Guokun Lai, Qizhe Xie, Hanxiao Liu, Yiming Yang, and Eduard Hovy. 2017. Race: Large-scale reading comprehension dataset from examinations. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.04683.

- Aitor Lewkowycz, Anders Johan Andreassen, David Dohan, Ethan Dyer, Henryk Michalewski, Vinay Venkatesh Ramasesh, Ambrose Slone, Cem Anil, Imanol Schlag, Theo Gutman-Solo, Yuhuai Wu, Behnam Neyshabur, Guy Gur-Ari, and Vedant Misra. 2022. Solving quantitative reasoning problems with language models. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems.

- Opher Lieber, Or Sharir, Barak Lenz, and Yoav Shoham. 2021. Jurassic-1: Technical details and evaluation. White Paper. AI21 Labs, 1. Stephanie Lin, Jacob Hilton, and Owain Evans. 2021. Truthfulqa: Measuring how models mimic human falsehoods. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.07958.

- Ilya Loshchilov and Frank Hutter. 2017. Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.05101. Matthew V Mahoney. 1999. Text compression as a test for artificial intelligence. AAAI/IAAI, 970.

- Todor Mihaylov, Peter Clark, Tushar Khot, and Ashish Sabharwal. 2018. Can a suit of armor conduct electricity? a new dataset for open book question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.02789.

- Tomas Mikolov, Martin Karafiát, Lukas Burget, Jan Cernocky, and Sanjeev Khudanpur. 2010. Recurrent neural network based language model. In Interspeech, pages 1045–1048. Makuhari.

- Nikita Nangia, Clara Vania, Rasika Bhalerao, and Samuel R. Bowman. 2020. CrowS-pairs: A challenge dataset for measuring social biases in masked language models. In EMNLP 2020.

- Erik Nijkamp, Bo Pang, Hiroaki Hayashi, Lifu Tu, Huan Wang, Yingbo Zhou, Silvio Savarese, and Caiming Xiong. 2022. Codegen: An open large language model for code with multi-turn program synthesis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.13474.

- Long Ouyang, Jeffrey Wu, Xu Jiang, Diogo Almeida, CarrollWainwright, Pamela Mishkin, Chong Zhang, Sandhini Agarwal, Katarina Slama, Alex Gray, John Schulman, Jacob Hilton, Fraser Kelton, Luke Miller, Maddie Simens, Amanda Askell, Peter Welinder, Paul Christiano, Jan Leike, and Ryan Lowe. 2022. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems.

- Markus N Rabe and Charles Staats. 2021. Selfattention does not need o(n2) memory. arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.05682.

- Alec Radford, Karthik Narasimhan, Tim Salimans, Ilya Sutskever, et al. 2018. Improving language understanding by generative pre-training.

- Alec Radford, Jeffrey Wu, Rewon Child, David Luan, Dario Amodei, Ilya Sutskever, et al. 2019. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI blog, 1(8):9.

- Jack W. Rae, Sebastian Borgeaud, Trevor Cai, Katie Millican, Jordan Hoffmann, Francis Song, John Aslanides, Sarah Henderson, Roman Ring, Susannah Young, Eliza Rutherford, Tom Hennigan, Jacob Menick, Albin Cassirer, Richard Powell, George van den Driessche, Lisa Anne Hendricks, Maribeth Rauh, Po-Sen Huang, Amelia Glaese, Johannes Welbl, Sumanth Dathathri, Saffron Huang, Jonathan Uesato, John Mellor, Irina Higgins, Antonia Creswell, Nat McAleese, Amy Wu, Erich Elsen, Siddhant Jayakumar, Elena Buchatskaya, David Budden, Esme Sutherland, Karen Simonyan, Michela Paganini, Laurent Sifre, Lena Martens, Xiang Lorraine Li, Adhiguna Kuncoro, Aida Nematzadeh, Elena Gribovskaya, Domenic Donato, Angeliki Lazaridou, Arthur Mensch, Jean-Baptiste Lespiau, Maria Tsimpoukelli, Nikolai Grigorev, Doug Fritz, Thibault Sottiaux, Mantas Pajarskas, Toby Pohlen, Zhitao Gong, Daniel Toyama, Cyprien de Masson d’Autume, Yujia Li, Tayfun Terzi, Vladimir Mikulik, Igor Babuschkin, Aidan Clark, Diego de Las Casas, Aurelia Guy, Chris Jones, James Bradbury, Matthew Johnson, Blake Hechtman, LauraWeidinger, Iason Gabriel,William Isaac, Ed Lockhart, Simon Osindero, Laura Rimell, Chris Dyer, Oriol Vinyals, Kareem Ayoub, Jeff Stanway, Lorrayne Bennett, Demis Hassabis, Koray Kavukcuoglu, and Geoffrey Irving. 2021. Scaling language models: Methods, analysis & insights from training gopher.

- Colin Raffel, Noam Shazeer, Adam Roberts, Katherine Lee, Sharan Narang, Michael Matena, Yanqi Zhou, Wei Li, and Peter J Liu. 2020. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. The Journal of Machine Learning Research, 21(1):5485–5551.

- Jonathan S Rosenfeld, Amir Rosenfeld, Yonatan Belinkov, and Nir Shavit. 2019. A constructive prediction of the generalization error across scales. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.12673.

- Rachel Rudinger, Jason Naradowsky, Brian Leonard, and Benjamin Van Durme. 2018. Gender bias in coreference resolution. In NAACL-HLT 2018.

- Keisuke Sakaguchi, Ronan Le Bras, Chandra Bhagavatula, and Yejin Choi. 2021. Winogrande: An adversarial winograd schema challenge at scale. Communications of the ACM, 64(9):99–106.

- Maarten Sap, Hannah Rashkin, Derek Chen, Ronan LeBras, and Yejin Choi. 2019. Socialiqa: Commonsense reasoning about social interactions. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.09728.

- Teven Le Scao, Angela Fan, Christopher Akiki, Ellie Pavlick, Suzana Ili´c, Daniel Hesslow, Roman Castagné, Alexandra Sasha Luccioni, François Yvon, Matthias Gallé, et al. 2022. Bloom: A 176bparameter open-access multilingual language model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.05100.

- Rico Sennrich, Barry Haddow, and Alexandra Birch. 2015. Neural machine translation of rare words with subword units. arXiv preprint arXiv:1508.07909.

- Claude E Shannon. 1948. A mathematical theory of communication. The Bell system technical journal, 27(3):379–423.

- Claude E Shannon. 1951. Prediction and entropy of printed english. Bell system technical journal, 30(1):50–64.

- Noam Shazeer. 2020. Glu variants improve transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2002.05202.

- Emily Sheng, Kai-Wei Chang, Premkumar Natarajan, and Nanyun Peng. 2019. The woman worked as a babysitter: On biases in language generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.01326.

- Mohammad Shoeybi, Mostofa Patwary, Raul Puri, Patrick LeGresley, Jared Casper, and Bryan Catanzaro. 2019. Megatron-lm: Training multi-billion parameter language models using model parallelism. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.08053.

- Shaden Smith, Mostofa Patwary, Brandon Norick, Patrick LeGresley, Samyam Rajbhandari, Jared Casper, Zhun Liu, Shrimai Prabhumoye, George Zerveas, Vijay Korthikanti, Elton Zhang, Rewon Child, Reza Yazdani Aminabadi, Julie Bernauer, Xia Song, Mohammad Shoeybi, Yuxiong He, Michael Houston, Saurabh Tiwary, and Bryan Catanzaro. 2022. Using deepspeed and megatron to train megatron-turing nlg 530b, a large-scale generative language model.

- Jianlin Su, Yu Lu, Shengfeng Pan, Ahmed Murtadha, Bo Wen, and Yunfeng Liu. 2021. Roformer: Enhanced transformer with rotary position embedding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.09864.

- Romal Thoppilan, Daniel De Freitas, Jamie Hall, Noam Shazeer, Apoorv Kulshreshtha, Heng-Tze Cheng, Alicia Jin, Taylor Bos, Leslie Baker, Yu Du, YaGuang Li, Hongrae Lee, Huaixiu Steven Zheng, Amin Ghafouri, Marcelo Menegali, Yanping Huang, Maxim Krikun, Dmitry Lepikhin, James Qin, Dehao Chen, Yuanzhong Xu, Zhifeng Chen, Adam Roberts, Maarten Bosma, Vincent Zhao, Yanqi Zhou, Chung-Ching Chang, Igor Krivokon, Will Rusch, Marc Pickett, Pranesh Srinivasan, Laichee Man, Kathleen Meier-Hellstern, Meredith Ringel Morris, Tulsee Doshi, Renelito Delos Santos, Toju Duke, Johnny Soraker, Ben Zevenbergen, Vinodkumar Prabhakaran, Mark Diaz, Ben Hutchinson, Kristen Olson, Alejandra Molina, Erin Hoffman-John, Josh Lee, Lora Aroyo, Ravi Rajakumar, Alena Butryna, Matthew Lamm, Viktoriya Kuzmina, Joe Fenton, Aaron Cohen, Rachel Bernstein, Ray Kurzweil, Blaise Aguera-Arcas, Claire Cui, Marian Croak, Ed Chi, and Quoc Le. 2022. Lamda: Language models for dialog applications.

- A. M. Turing. 1950. Computing Machinery and Intelligence. [Oxford University Press, Mind Association].

- Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N Gomez, Ł ukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. 2017. Attention is all you need

- Ben Wang and Aran Komatsuzaki. 2021. GPT-J-6B: A 6 Billion Parameter Autoregressive Language Model. https://github.com/kingoflolz/mesh-transformer-jax.

- Xuezhi Wang, Jason Wei, Dale Schuurmans, Quoc Le, Ed Chi, Sharan Narang, Aakanksha Chowdhery, and Denny Zhou. 2022. Self-consistency improves chain of thought reasoning in language models.

- Jason Wei, Yi Tay, Rishi Bommasani, Colin Raffel, Barret Zoph, Sebastian Borgeaud, Dani Yogatama, Maarten Bosma, Denny Zhou, Donald Metzler, et al. 2022. Emergent abilities of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.07682.

- Guillaume Wenzek, Marie-Anne Lachaux, Alexis Conneau, Vishrav Chaudhary, Francisco Guzmán, Armand Joulin, and Edouard Grave. 2020. CCNet: Extracting high quality monolingual datasets from web crawl data. In Language Resources and Evaluation Conference.

- Carole-Jean Wu, Ramya Raghavendra, Udit Gupta, Bilge Acun, Newsha Ardalani, Kiwan Maeng, Gloria Chang, Fiona Aga, Jinshi Huang, Charles Bai, et al. 2022. Sustainable ai: Environmental implications, challenges and opportunities. Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems, 4:795–813.

- Rowan Zellers, Ari Holtzman, Yonatan Bisk, Ali Farhadi, and Yejin Choi. 2019. Hellaswag: Can a machine really finish your sentence? arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.07830.

- Aohan Zeng, Xiao Liu, Zhengxiao Du, Zihan Wang, Hanyu Lai, Ming Ding, Zhuoyi Yang, Yifan Xu, Wendi Zheng, Xiao Xia, Weng Lam Tam, Zixuan Ma, Yufei Xue, Jidong Zhai, Wenguang Chen, Peng Zhang, Yuxiao Dong, and Jie Tang. 2022. Glm-130b: An open bilingual pre-trained model.

- Biao Zhang and Rico Sennrich. 2019. Root mean square layer normalization. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 32.

- Susan Zhang, Stephen Roller, Naman Goyal, Mikel Artetxe, Moya Chen, Shuohui Chen, Christopher Dewan, Mona Diab, Xian Li, Xi Victoria Lin, et al. 2022. Opt: Open pre-trained transformer language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.01068.

附录(略)

见原文。