Ctrip Network Architecture Evolution in the Cloud Computing Era

Preface

This article comes from my talk Ctrip Network Architecture Evolution in the Cloud Computing Era in GOPS 2019 Shenzhen (a tech conference in Chinese).

中文版:云计算时代携程的网络架构变迁。

- Preface

- About Me

- 0 About Ctrip Cloud

- 1 VLAN-based L2 Network

- 2 SDN-based Large L2 Network

- 3 K8S & Hybrid Cloud Network

- 4 Cloud Native Solutions

- References

About Me

I’m a senior achitect at Ctrip cloud, currently lead the network & storage development team, focusing on network virtualization and distributed storage.

0 About Ctrip Cloud

Ctrip’s cloud computing team started at ~2013.

We started our business by providing compute resources to our internal customers based on OpenStack. Since then, we have developed our own baremetal platform, and further, deployed container platforms like Mesos and K8S.

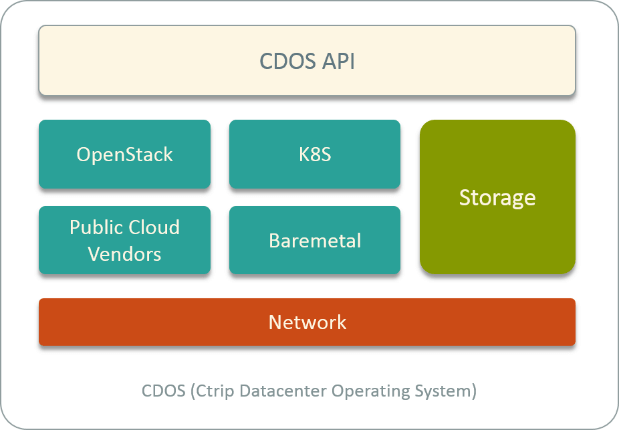

In recent years, we have packed all our cloud services into a unified platform, we named it CDOS - Ctrip Datacenter Operating System.

Fig 1. Ctrip Datacenter Operation System (CDOS)

CDOS manages all our compute, network and storage resources on both private and public cloud (from vendors). In the private cloud, we provision VM, BM and container instances. In the public cloud, we have integrated public cloud vendors like AWS, Tecent cloud, UCloud, etc to provide VM and container instances to our internal customers.

Network Evolution Timeline

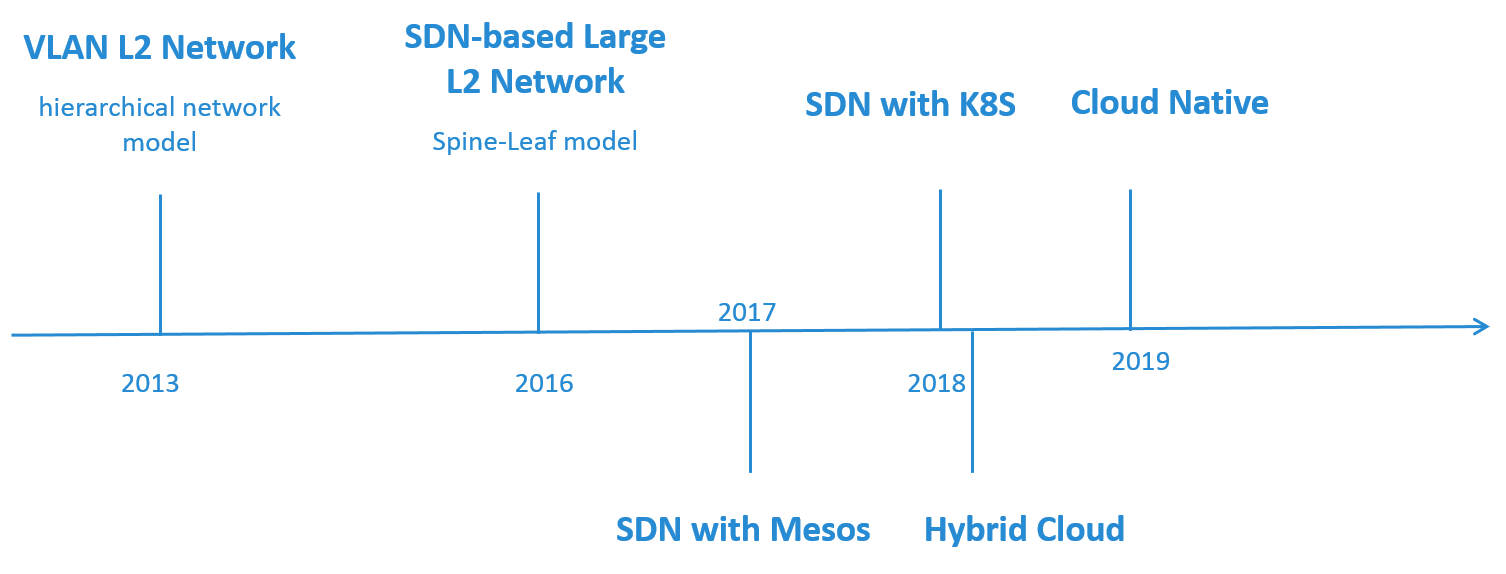

Fig 2. Timeline of the Network Architecture Evolution

Fig 2 is a rough timeline of our network evolution.

At 2013, we started building our private cloud based on OpenStack, and we chose a simple VLAN-based L2 network model. The underlying HW network topolopy was traditional hierarchical network model (3-layer network model).

At 2016, we evolved to a SDN-based large L2 network, and the underlying HW network evolved to Spine-Leaf model.

Starting from 2017, we began to deploy container platforms (mesos, k8s) on both private and public cloud. In the private cloud, we extended our SDN solution to integration container networks. On the public cloud, we also designed our container network solution, and connected the public and private cloud.

Now (2019), we are doing some investigations on cloud native solutions to address the new challenges we are facing.

Let’s dig into those solutions in more detail.

1 VLAN-based L2 Network

At 2013, we started building our private cloud based on OpenStack, provisioning VM and BM instances to our internal customers.

1.1 Requirements

The requirements for network were as follows:

First, performance of the virtualized network should not be too bad compared with baremetal networks, measuring with metrics such as instance-to-instance latency, throughput, etc.

Secondly, it should have some L2 isolations to prevent common L2 problems e.g. flooding.

Thirdly, and this is really important - the instance IP should be routable. That is to say, we could not utilize any tunnling techniques within the host.

At last, security concerns were less critical at that time. If sacrificing a little security could give us a significant performance increase, that would be acceptable. As in a private cloud environment, we have other means to ensure security.

1.2 Solution: OpenStack Provider Network Model

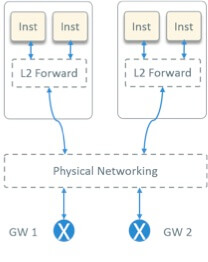

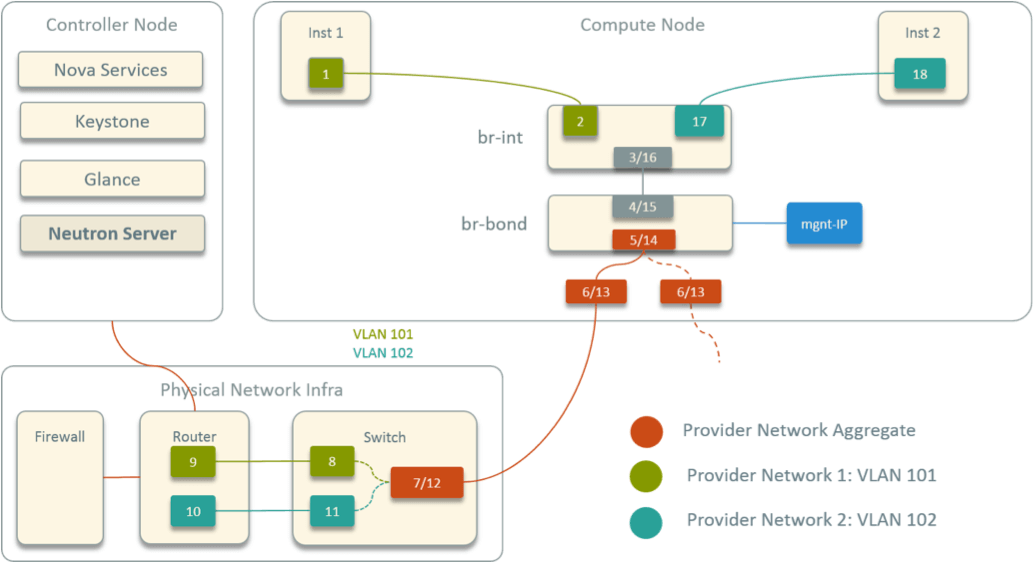

Fig 3. OpenStack Provider Network Model

After some investigation, we chose the OpenStack provider network model [1], as depicted in Fig 3.

The provider network model has following characteristics:

- L2 forwarding within host, L2 forwarding + L3 routing outside host

- Tenant gateways configured on HW devices. So this is a SW + HW solution, rather than a pure SW solution

- Instance IP routable

- High performance. This comes mainly from two aspects:

- No overlay encapsulation/decapsulation

- Gateways configured on HW device, which has far more better performance compared with SW implemented virtual routers (L3 agent) in OpenStack

Other aspects in our design:

- L2 segmentation: VLAN

- ML2: OVS

- L2 Agent:Neutron OVS Agent

- L3 Agent: NO

- DHCP: NO

- Floating IP: NO

- Security Group:NO

1.3 HW Network Topology

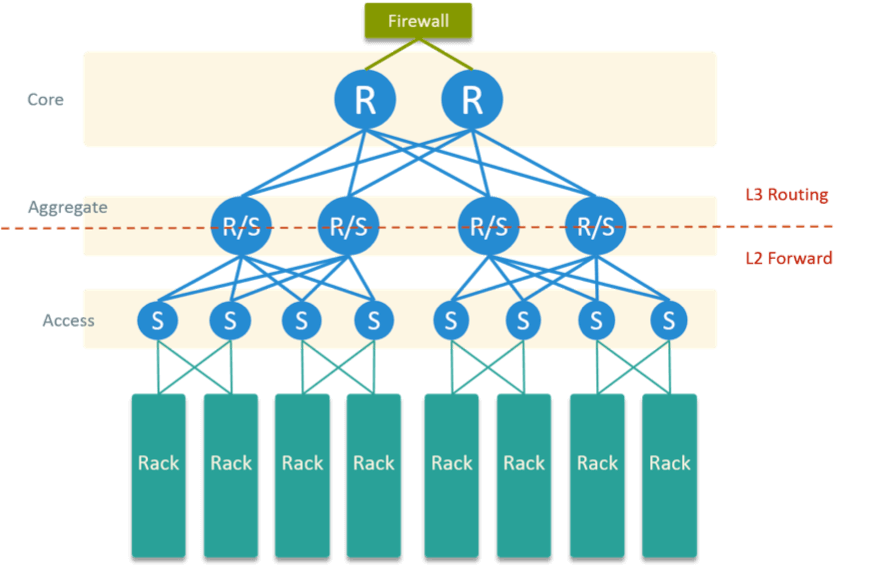

The HW network topology in our data center is Fig 4.

Fig 4. Physical Network Topology in the Datacenter

The bottom part are rack rows. Each blade in the rack had two physical NIC, connected to two adjacent ToR for physical HA.

The above part is a typical access - aggregate - core hierarchical network model. Aggregate layer communicates with access layer via L2 forwarding, and with core layer via L3 routing.

All OpenStack network gateways are configured on core routers. Besides, there are HW firewalls connected to core routers to perform some security enforcements.

1.4 Host Network Topology

The virtual network topology within a compute node is shown in Fig 5.

Fig 5. Designed Virtual Network Topology within A Compute Node

Some highlights:

- Two OVS bridges

br-intandbr-bond, connected directly - Two physical NICs bonded into one virtual device, attached to

br-bond - Host IP address also configured on

br-bond, serving as management IP - All instance devices (virtual NICs) attached to

br-int

In the picture, inst1 and inst2 are two instances from different networks.

The numbered devices started from inst1 and ended at inst2 is just the

packet traversing path between the two (cross network) instances. As can be

seen, there are 18 hops in total.

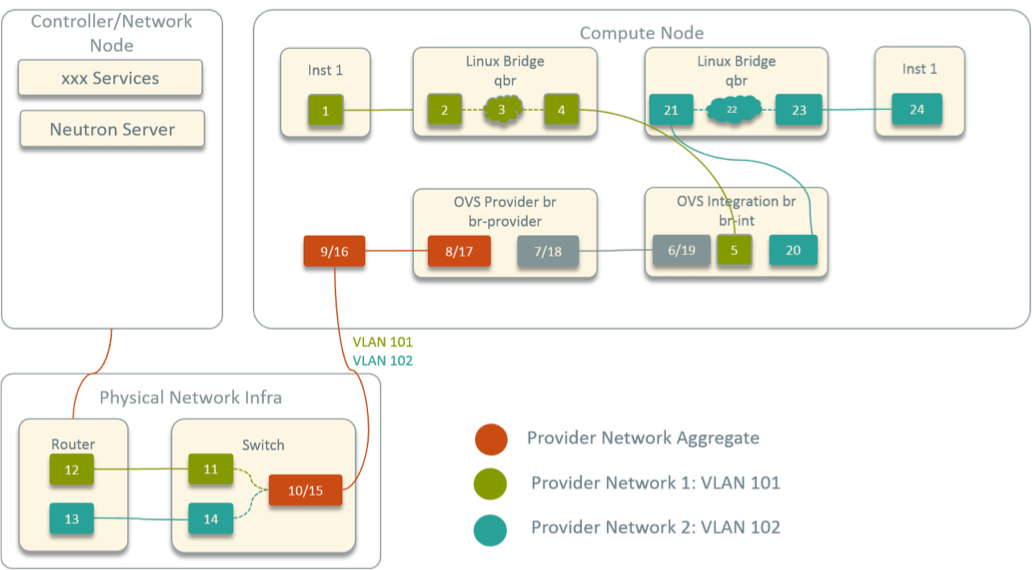

In contrast, Fig 6 shows the topology in legacy OpenStack provider network model.

Fig 6. Virtual Network Topology within A Compute Node in Legacy OpenStack

The biggest difference here is: a Linux bridge sits between each instance

and br-int. This is because OpenStack supports a feature called “security

group”, which uses iptables in the behind. Unfortunately, OVS ports do not

support iptables rules; but Linux bridge ports do support, so in OpenStack

a Linux bridge is inserted between each instance and br-int.

Except this, other parts are similar, so in this circumstance, the total hops is 24.

1.5 Summary

Advantages

First of all, we simplified OpenStack deployment architecture, removed some components that we did not need, e.g. L3 agent, DHCP agent, Neutron metadata agent, etc, and we no longer needed a standalone network node. For a team which just started private cloud with not so much experience, the developing and operating costs became relatively low.

Secondly, we simplified the host network topology by removing security groups. The total hops between two instances from different networks was decreased from 24 to 18, thus has lower latency.

Thirdly, we had our gateways configured on HW devices, which had far more better performance than OpenStack’s pure SW solutions.

And at last, the instance IP was routable, which benifited a lot to upper layer systems such as tracking and monitoring systems.

Disadvantags

First, as has been said, we removed security groups. So the security is sacrified at some extent. We compensated this partly by enforcing some security rules on HW firewalls.

Secondly, the network provision process was less automatic. For example, we had to configure the core routers whenever we add/delete networks to/from OpenStack. Although these operations have a very low frequency, the impact of core router misconfiguration is dramatic - it could affect the entire network.

2 SDN-based Large L2 Network

2.1 New Challenges

Time arrived 2016, due to the scale expansion of our cluster and network, the VLAN-based L2 network reached some limitations.

First of all, if you are familiar with data center networks you may know that hierachical network model is hard to scale.

Secondly, all the OpenStack gateways were configured on the core routers, which made them the potential bottleneck and single point of failure. And more, core router failures will disrupt the entire network, so the failure radius is very large.

Another limitation is that our blade was equipped with 2 x 1 Gbps NICs, which was too old for modern data center and morden applications.

Besides, the VLAN has its own limitations: flooding in large VLAN segmentations is still a problem, and number of avialble VLAN IDs is less than 4096.

On the other hand, we had also some new needs, as such:

- Our corp acquired some companies during the past years, and the networks of those companies needed to connect/integrate to ours. At network level, we’d like to treat those subsidiary companies as tenants, so we had multitenancy and VPC needs.

- We’d like the network provision more automatic, with little human intervention.

2.2 Solution: OpenStack + SDN

Regarding to these requirements, we designed a HW+SW, OpenStack+SDN solution jointly with the data center network team in our corporation, shifted the network from L2 to Large L2.

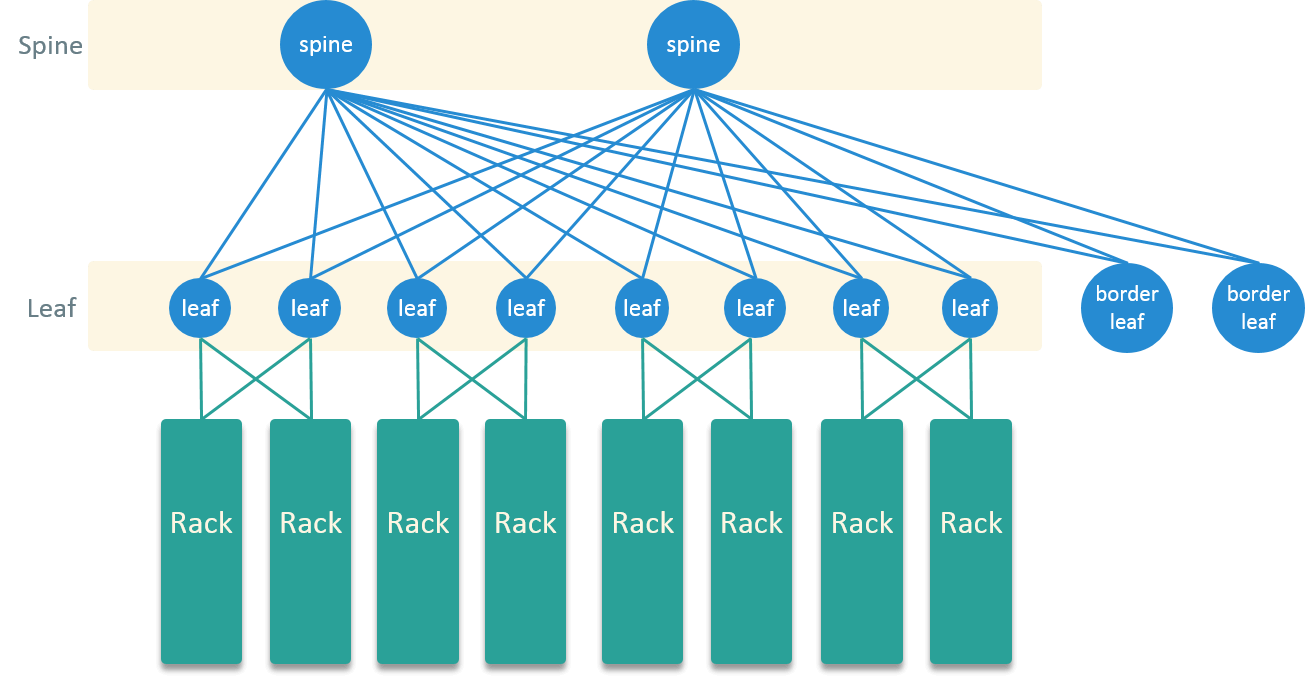

HW Topology

For the HW network topology, we evolved from the traditional 3-layer hierachical model to Spine-Leaf model, which gets more and more popular in modern data centers.

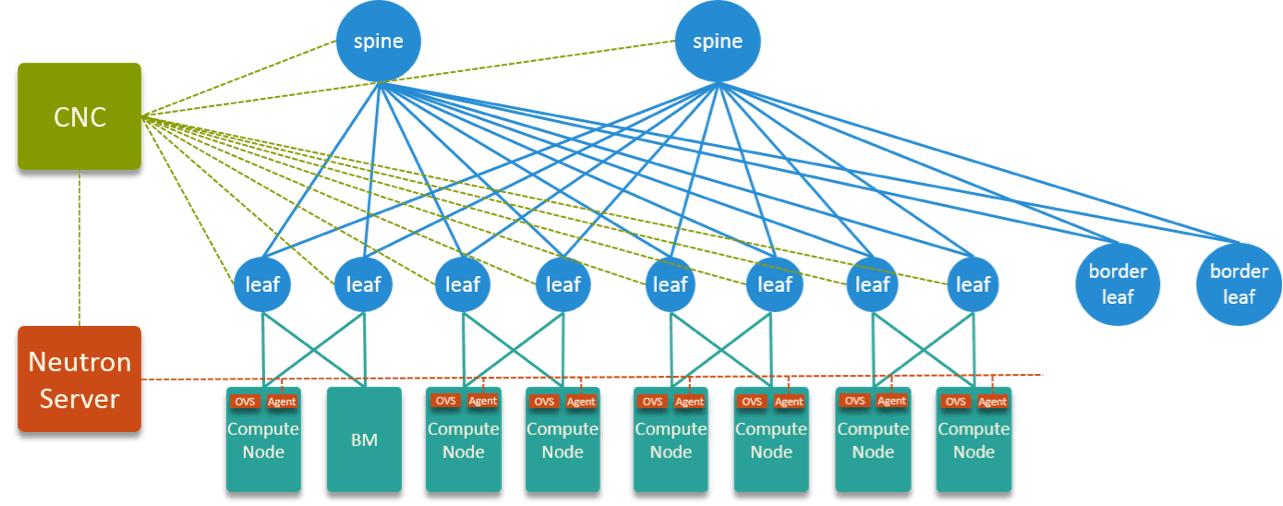

Fig 7. Spine-Leaf Topology in the New Datacenter

Spine-Leaf model is full-mesh connected, which means every device in Spine layer connects to every device in Leaf layer, and there is no connectitiy among nodes in the same layer. This connectivity pattern brings many benifits:

- Shorter traversing path and estimable latency: a server could reach any other server in exactly 3 hops (server-to-server latency)

- Ease of expansing: to increase the bandwidth, just add a node in one layer and connect it to all other nodes in the other layer

- More resilent to HW failures: all nodes are active, node failure radius is far more smaller than in hierachical model

For blades, we upgraded the NICs to 10 Gbps, and further to 25 Gbps.

SDN: Control and Data Plane

We have separate control and data planes [2]:

- Data plane: VxLAN

- Control plane: MP-BGP EVPN

These are standard RFC protocols, refer to [2] for more protocol details and use cases.

One additional benefit of this model is that it supports distributed gateway, which means all leaf nodes are acted as (active) gateways, which eliminates the performance bottleneck of traditional gateways on core routers.

This solution physically support multitenancy (via VRF).

SDN: Components And Implementation

We developed our own SDN controller Ctrip Network Controller (CNC).

CNC is a central SDN controller, and manges all Spine and Leaf nodes. It integrates with Neutron server via Neutron plugins, and is able to dynamically add configurations to Spine/Leaf nodes.

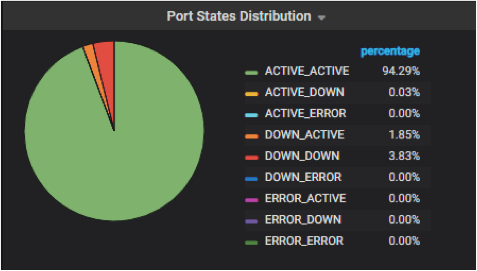

Neutron changes:

- Add CNC ML2 & L3 plugins

- New finite state machine (FSM) for port status

- New APIs interact with CNC

- DB schema changes

Below is the monitoring panel for the neutron port states in a real data center.

Fig 8. Monitoring Panel for Neutron Port States

2.3 HW + SW Topology

Fig 9. HW + SW Topology of the Designed SDN Solution

Fig 9 is the overall HW + SW topology.

VxLAN encap/decap is done on the leaf nodes. If we draw a horizeontal line to cross all Leaf nodes, this line splits the entire network into underlay and overlay. The bottom part (below leaf) belongs to underlay and is isolated by VLAN; The above part (above leaf) is overlay and isolated by VxLAN.

Underlay is controlled by Neutron server, OVS and neutron-ovs-agent, overlay is controlled by CNC. CNC integrates with Neutron via Neutron plugins.

As has been said, this is a joint work by cloud network team & data center network team. We cloud network team focuses mainly on the underlay part.

2.4 Spawn An Instance

In this solution, when spawning an instance, how the instance’s network gets reachable?

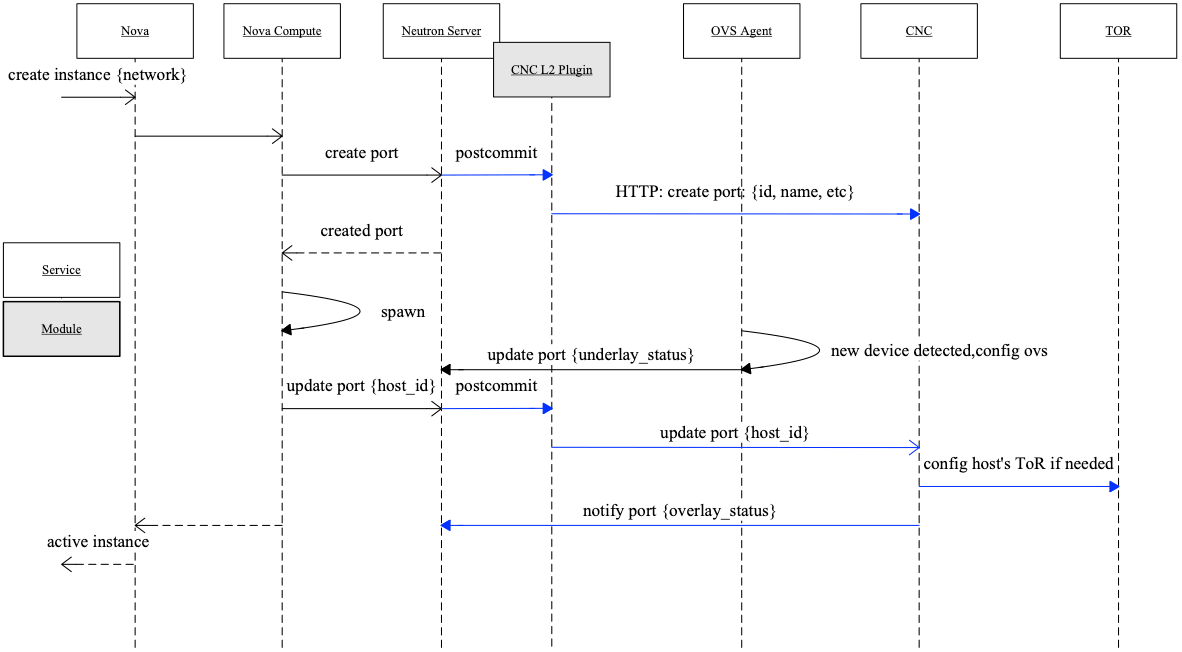

Fig 10. Flow of Spawn An Instance

Major steps depicted in Fig 10:

- Nova API (controller node): Create instance -> schedule to one compute node

- Nova compute: spawn instance on this node

- Nova compute -> Neutron server: create neutron port

- Neutron server: create port (IP, MAC, GW, etc)

- Neutron server -> CNC plugin -> CNC: send port info

- CNC: save port info to its own DB

- Neutron server -> Nova compute: return the created port’s info

- Nova compute: create network device (virtual NIC) for instance, configure device (IP, MAC, GW, etc), then attach it to OVS

- OVS agent: detect new device attached -> configure OVS (add flow) -> Underlay network OK

- Nova compute -> Neutron server: update port

host_id. The message is something like this: port1234is on hostnode-1 - Neutron server -> CNC: update port

host_id, something like this: port1234is on hostnode-1 - CNC: retrieve database, get the leaf interfaces that

node-1connected to, dynamically add configurations to these interfaces -> Overlay network OK - Both underlay and overlay networks OK -> instance reachable

In Fig 10, black lines are legacy OpenStack flows, and blue lines are newly added by us.

2.5 Summary

A summary of the SDN-based large L2 network solution.

HW

First, HW network model evolved from hierarchical (3-layer) network to Spine-Leaf (2-tier). With the Spine-Leaf full-mesh connectivity, server-to-server latency gets more lower. Spine-Leaf also supports distributed gateway, which means all leaf nodes act as gateway for the same network, not only decreased the traversing path, but also alleviated the bottleneck of central gateways.

Another benefit of full-mesh connectivity is that the HW network are now more resilient to failures. All devices are active rather than active-backup (traditional 3-layer model), thus when one device fails, it has far more smaller failure radius.

SW

For the SW part, we developed our own SDN controller, and integrated it with OpenStack neutron via plugins. The SDN controller cloud dynamically send configurations to HW devices.

Although we have only mentioned VM here, this solution actually supports both VM and BM provision.

Multi-tenancy & VPC support

At last, this solution supports multi-tenancy and VPC.

3 K8S & Hybrid Cloud Network

At 2017, we started to deploy container platforms, migrating some applications from VM/BM to containers.

Container orchestrators (e.g. Mesos, K8S) has different characteristics compared with VM orchestrator (e.g OpenStack), such as:

- Large scale instances, 10K ~ 100K containers per cluster is commonly seen

- Higher deploy/destroy frequencies

- Shorter spawn/destroy time: ~10s (VM: ~100s)

- Container failure/drifting is the norm rather than exception

3.1 K8S Network In Private Cloud

Characteristics of container platform raised new requirements to the network.

3.1.1 Network Requirements

First, The network API must be high performance, and supporting concurrency.

Secondly, whether using an agent or a binary to configure network (create vNICs and configure them), it should be fast enough.

To sucessfully sell container platforms to our customers, we must keep a considerable amount of compatibility with existing systems.

One of these is: we must keep the IP address unchanged when container drifts from one node to another. This is an anti-pattern to container platform’s philosophy, as those orchestrators are desgined to weaken the IP address: users should only see the service that a container exposed, but not the IP address of a single container. The reason why we have to comprimise here is that in OpenStack age, VM migration keeps the IP unchanged. So lots of outer systems assumed that IP address is an immutable attribute of an instance during its lifecycle, and they designed their systems based on this assumption. If we suddenly break this assumption, lots of systems (SOA, SLB, etc) need to be refactored, and this is out of our control.

3.1.2 Solution: Extend SDN to Support Mesos/K8S

In private cloud, we decided to extend our SDN solution to integrate container networks. We reused existing infrastructures, including Neutron, CNC, OVS, Neutron-OVS-Agent. And then developed a CNI plugin for neutron.

Some changes or newly added components listed below.

Neutron Changes

First, we added some new APIs, e.g. legacy Neutron supports only allocating port

by network ID, we added label attributes to Neutron networks model, supporting

allocating port by network labels. For example, CNI plugin will say, “I want

a port allocated from any network with ‘prod-env’ label”. This decouples K8S

from OpenStack details and is more scalable, because a label could mapping to

any number of networks.

Next, we did some performance optimizations:

- Add Bulk port API

- Database access optimizations

- Async API for high concurrency

- Critical path refactor

We also backported some new features from upstream, e.g. graceful OVS agent restart, a big benefit for network operators.

New K8S CNI plugin for neutron

K8S CNI plugin creates and deletes networks for each Pod. The jobs it does are much the same with other CNI plugins (e.g Calico, Flannel): creates veth pair, attaches to OVS and container netns, configures MAC, IP, GW, etc.

Two big differences seperating it from other plugins:

- Communicate with Neutron (central IPAM) to allocate/free port (IP address)

- Update port information to neutron server after finishing

Existing network services/components upgrade

We also upgraded some network infra. E.g. we’ve hit some OVS bugs during past few years:

- ovs-vswitchd 100% CPU bug [3]

- OVS port mirror bug [4]

So we upgraded OVS to the latest LTS 2.5.6, which has solved those bugs.

3.1.3 Pod Drifting

Network steps in starting a container are much the same as in spawning a VM in Fig. 10, so we do not detail it here.

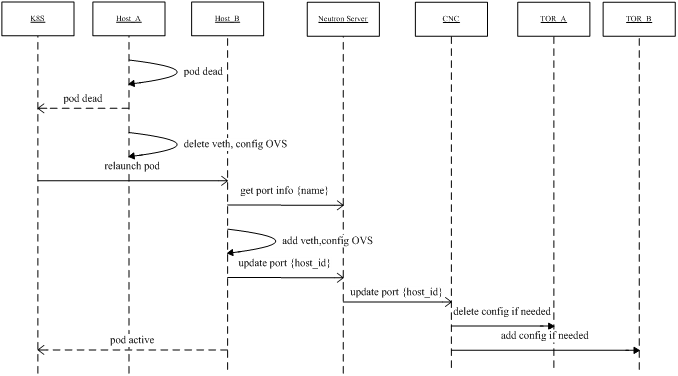

Fig 11 shows how the IP address stayed unchanged during container drifting. The

key point is: CNI plugin knows how to join some Pod labels into a port name.

This name is unique index, so the second node (node B) could get the IP

address information from neutron with this name.

Fig 11. Pod drifting with the same IP within a K8S cluster

3.1.4 Summary

A quick summary:

- We integrated container platform into existing infra in a short time

- Single global IPAM manages all VM/BM/container networks

Sum up, this is the latest network solution int private cloud.

Current deployment scale of this new solution:

- 4 availability zones (AZ)

- Up to 500+ physical nodes (VM/BM/Container hosts) per AZ

- Up to 500+ instances per host

- Up to 20K+ instances per AZ

3.1.5 Future Architecture

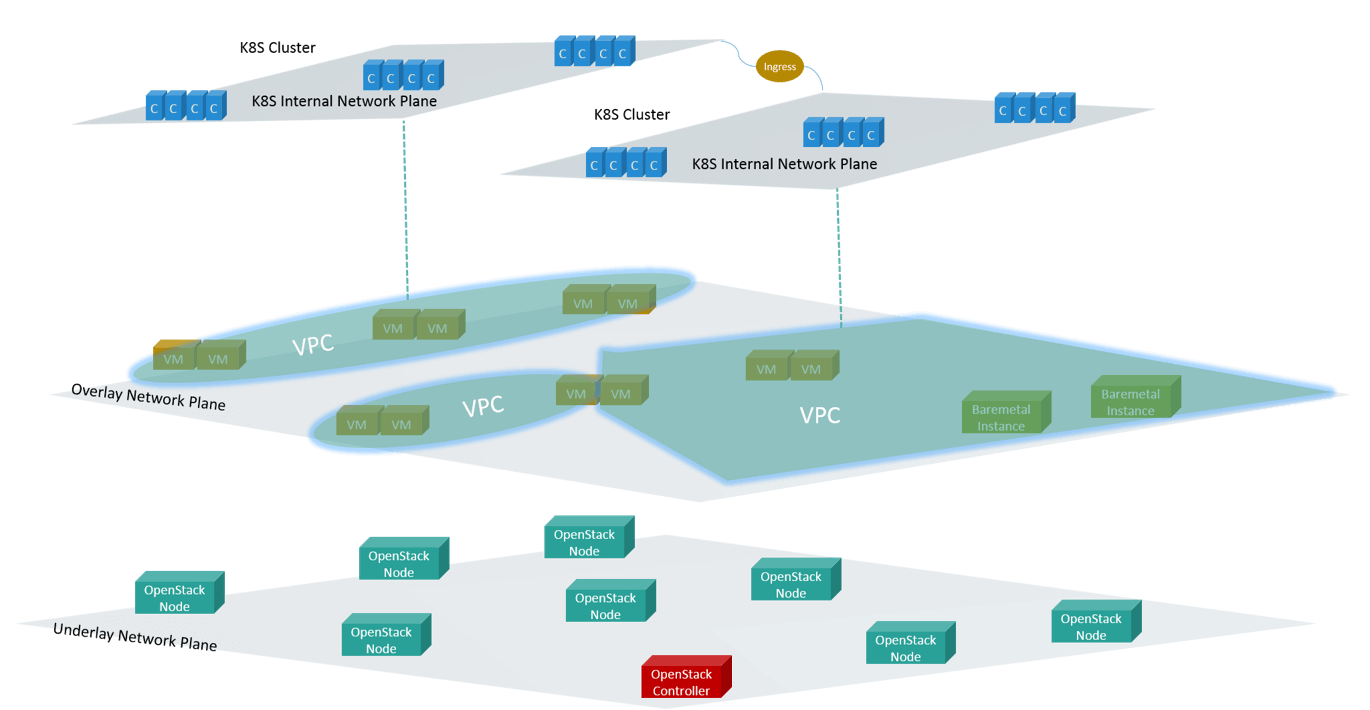

Fig 12. Layered view of the future network architecture

Fig 12 is an architucture we’d like to achieve in the future.

First, the network will be split into underlay and overlay planes. IaaS and other Infra services deploy in underlay network, e.g OpenStack, CNC. Then creating VPC in overlay networks, and deploying VM and BM instances in VPCs. These have been achieved.

One K8S cluster will be kept within one VPC, and each cluster manages its own networks. All access via IP address should be kept within that cluster, and all access from outside of the cluster should go through Ingress - the K8S native way. We haven’t achieved this, because it needs lots of SW and HW system refactors.

3.2 K8S on Public Cloud

3.2.1 Requirements

Ctrip started its internationalization in recent years, in the techical layer, we should be able to support global deployment, which means provisioning resources outside mainland China.

Building overseas private cloud is not practical, as the designing and building process will take too much time. So we chose to purchase public cloud resources, deploy and manage our own K8S clusters (rather than using vendor-managed clusters, e.g. AWS EKS [10]) and integrate them to our private cloud infra, turning CDOS into a hybrid cloud platform. CDOS API will abstract out all vendor-specific details, and provide a unified API to our internal customers/systems.

This work involves networking solutions on public cloud platforms.

3.2.2 K8S Network Solution on AWS

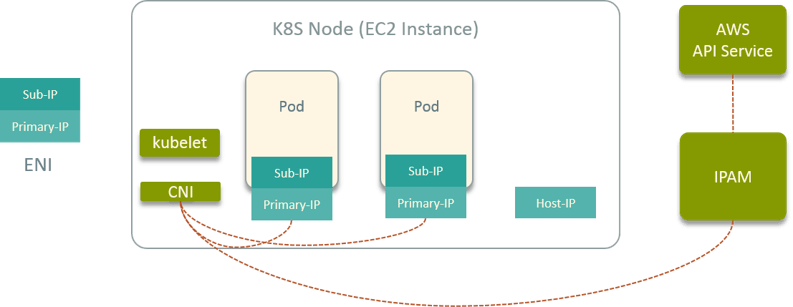

Taking AWS as example, let’s see our K8S network solution.

Fig 13. K8S network solution on public cloud vendor (AWS)

First, spawning EC2 instances as K8S nodes on AWS. Then we developed a CNI plugin to dynamically plug/unplug ENI to EC2 [5, 6]. The ENIs were given to Pods as its vNIC.

We developed a global IPAM service (just like Neutron in OpenStack) and deployed in VPC, it manages all network resources, and calls AWS APIs for real allocation/deallocation.

The CNI plugin also supports attach/detach floating IP to Pods. And again, the IP address stays the same when Pod drifts from one node to another. This is achieved by ENI drifting.

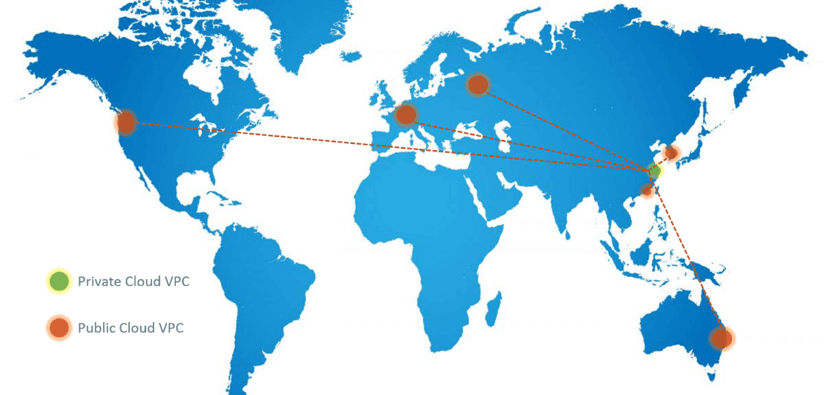

3.2.3 VPCs over the globe

Fig 14 is the global picture of our VPCs in both private and public cloud.

We have some VPCs in our private cloud distributed in Shanghai and Nantong. Outside mainland China, we have VPCs on public cloud regions, including Seoul, Moscow, Frankfurt, California, Hong Kong, Melborne, and many more.

Fig 14. VPCs distributed over the globe

Network segments of VPCs on both prviate and public cloud are arranged to be non-overlapped, so we connect them with direct connect techniques, and the IP is routable (if needed).

OK, right here, I have introduced all of the major aspects of our network evolution. In the next, let’s see some new challenges in the cloud native age.

4 Cloud Native Solutions

The current network solution faced some new challenges in cloud native era:

- Central IPAM may be the new bottleneck, and Neutron is not designed for performance

- Cloud native prefers local IPAM (IPAM per host)

- Large failure radius: IP drifting among entire AZ

- Dense deployment of containers will hit HW limit of leaf nodes

- Increasingly strong host firewall (L4-L7) needs

So we are doing some investigations on new solutions, e.g. Calico, Cilium. Calico has been widely used nowadays, so I’ll skip it and give some introduction to a relatively less well-known solution: Cilium.

4.1 Cilium Overview

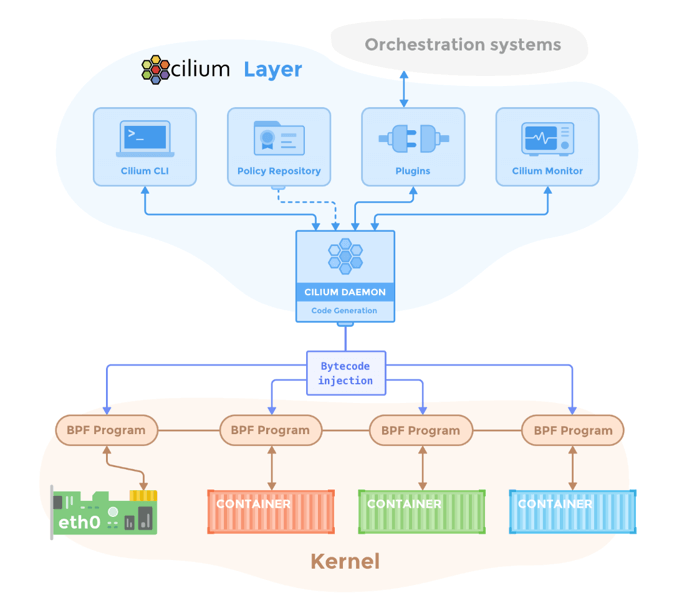

Cilium is a brand-new solution [7], and it needs Kernel 4.8+.

Cilium’s core relies on eBPF/BPF, which is a bytecode sandbox in Linux kernel. If you never heard of this, think BPF as iptables, it could hook and modify packets in the kernel stack, we will tell the difference later.

Cilium relies on BPF to achieve connectivity & security. It has following components:

- CLI

- Plugin for orchestrator (Mesos, K8S, etc) integration

- Policy repository (etcd or consul)

- Host agent (also acts as local IPAM)

Fig 15. Cilium

4.2 Host Networking

Any networking solution could be split into two major parts:

- Host-networking: instance-to-instance communication, and instance-to-host communication

- Multi-host-networking: cross-host and/or cross-subnet instance-to-instance communication

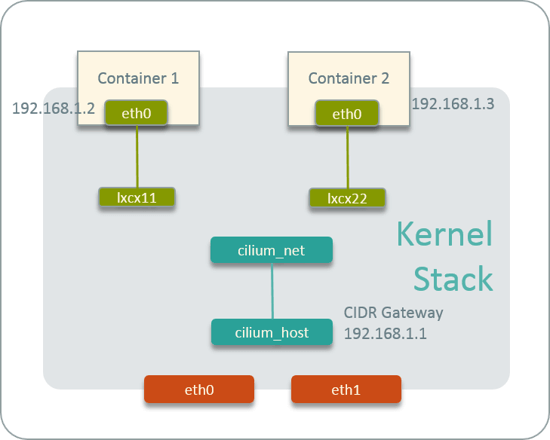

Let’s see the host-networking of Cilium.

Fig 16. Cilium host-networking

First, each host runs a Cilium agent, the agent acts as local IPAM, and manages its CIDR.

Upon starting, it creates a veth pair named cilium_host <--> cilium_net, and

sets the first IP address of the CIDR to cilium_host, which then acts as the

gateway of the CIDR.

When starting a Pod in this host, the CNI plugin will:

- allocate an IP address from this CIDR

- create a veth pair for the Pod

- configure the IP, gateway info to Pod

Then the topology will look like Fig 16. Note that there is no OVS or

Linux bridges among the Pods’ veth pairs and cilium_host <--> cilium_net.

Actually there are also no special ARP entries or route entries to connect the

veth pairs. Then how does the packet been forwarded when it reaches the veth

pair end? The answer is BPF code. CNI plugin will generate BPF rules,

compile them and inject them into kernel to bridge the gaps between veth pairs.

Summary of cilium host networking:

- Inst-to-inst: BPF + Kernel Stack L2 forward

- Inst-to-host: BPF + L3 Routing

4.3 Multi-host networking

For multi-host networking, Cilium provides two commonly used ways:

- VxLAN overlay

- BGP direct routing

If using VxLAN, Cilium will create a cilium_vxlan device in each host, and do

VxLAN encap/decap by software. The performance will be a big concern, although

VxLAN HW offload will partly alleviate the burden.

BGP is another choice. In this case, you need to run a BGP agent in each host,

the BGP agent will do peering with outside network. This needs data center

network support. On public cloud, you could also try the BGP API.

BGP solution has better performance compared with VxLAN overlay, and more

importantly, it makes the container IP routable.

4.4 Pros & Cons

Here is a brief comparison according to my understanding and experiment.

Pros

- K8S-native L4-L7 security policy support

- High performance network policy enforcement

- Theoretical complexity: BPF O(1) vs iptables O(n) [11]

- High performance forwarding plane (veth pair, IPVLAN)

- Dual stack support (IPv4/IPv6)

- Support run over flannel (Cilium only handles network policy)

- Active community

- Development driven by a company

- Core developers from kernel community

Cons

Latest kernel (4.8+ at least, 4.14+ better) needed. lots of companies’ PROD environments run kernels older than this.

Not enough user stories & best practices yet. Everyone says Cilium is brilliant, but no one has claimed they have deployed Cilium at large scale in their PROD environments.

High dev & ops costs. Compared with iptables-based solutions, e.g. Calico, big companies usually have customization needs because all of reasons, e.g. compatibility with old systems to not break the business. The development would need a gentle understanding with kernel stack: you should be familir with kernel data structures, know the packet traversing path, have a considerable experience with C programming - BPF code is written in C.

Trouble shooting and debugging. You should equipped yourself with Cilium trouble shooting skills, which are different from iptables-based solutions. While in many cases, their maybe a shortage of proper trouble shooting tools.

But at last, Cilium/eBPF is still one of the most exciting techs rised in recent years, and it’s still under fast developing. So, have a try and find the fun!

References

- OpenStack Doc: Networking Concepts

- Cisco Data Center Spine-and-Leaf Architecture: Design Overview

- ovs-vswitchd: Fix high cpu utilization when acquire idle lock fails

- openvswitch port mirroring only mirrors egress traffic

- Lyft CNI plugin

- Netflix: run container at scale

- Cilium Project

- Cilium Cheat Sheet

- Cilium Code Walk Through: CNI Create Network

- Amazon EKS - Managed Kubernetes Service

- Cilium: API Aware Networking & Network Security for Microservices using BPF & XDP